Reposted from Variance Explained with minor modifications.

This post follows an earlier post on the same topic.

A year ago today, I wrote up a blog post Text analysis of Trump’s tweets confirms he writes only the (angrier) Android half.

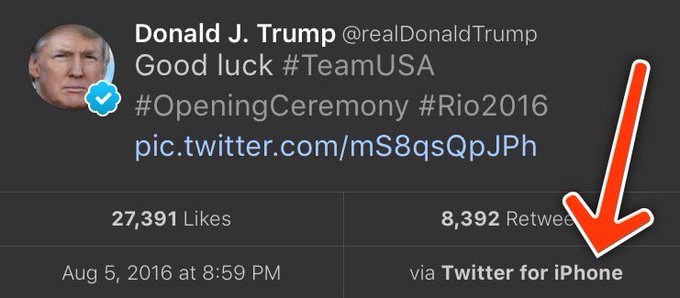

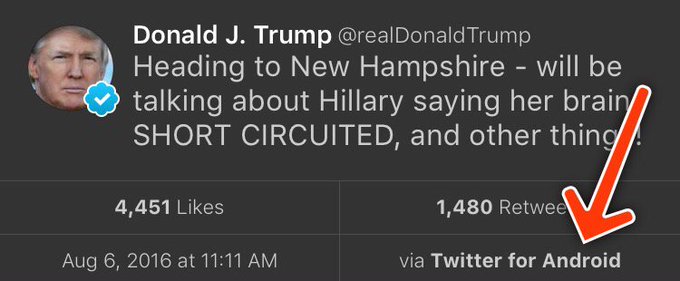

My analysis, shown below, concludes that the Android and iPhone tweets are clearly from different people, posting during different times of day and using hashtags, links, and retweets in distinct ways. What’s more, we can see that the Android tweets are angrier and more negative, while the iPhone tweets tend to be benign announcements and pictures.

Of course, a lot has changed in the last year. Trump was elected and inaugurated, and his Twitter account has become only more newsworthy. So it’s worth revisiting the analysis, for a few reasons:

- There is a year of new data, with over 2700 more tweets. And quite notably, Trump stopped using the Android in March 2017. This is why machine learning approaches like didtrumptweetit.com are useful since they can still distinguish Trump’s tweets from his campaign’s by training on the kinds of features I used in my original post.

- I’ve found a better dataset: in my original analysis, I was working quickly and used the twitteR package to query Trump’s tweets. I since learned there’s a bug in the package that caused it to retrieve only about half the tweets that could have been retrieved, and in any case, I was able to go back only to January 2016. I’ve since found the truly excellent Trump Twitter Archive, which contains all of Trump’s tweets going back to 2009. Below I show some R code for querying it.

- I’ve heard some interesting questions that I wanted to follow up on: These come from the comments on the original post and other conversations I’ve had since. Two questions included what device Trump tended to use before the campaign, and what types of tweets tended to lead to high engagement.

So here I’m following up with a few more analyses of the \@realDonaldTrump account. As I did last year, I’ll show most of my code, especially those that involve text mining with the tidytext package (now a published O’Reilly book!). You can find the remainder of the code here.

Updating the dataset

The first step was to find a more up-to-date dataset of Trump’s tweets. The Trump Twitter Archive, by Brendan Brown, is a brilliant project for tracking them, and is easily retrievable from R.

library(tidyverse)

library(lubridate)

url <- 'http://www.trumptwitterarchive.com/data/realdonaldtrump/%s.json'

all_tweets <- map(2009:2017, ~sprintf(url, .x)) %>%

map_df(jsonlite::fromJSON, simplifyDataFrame = TRUE) %>%

mutate(created_at = parse_date_time(created_at, "a b! d! H!:M!:S! z!* Y!")) %>%

tbl_df()As of today, it contains 31548, including the text, device, and the number of retweets and favourites. (Also impressively, it updates hourly, and since September 2016 it includes tweets that were afterwards deleted).

Devices over time

My analysis from last summer was useful for journalists interpreting Trump’s tweets since it was able to distinguish Trump’s tweets from those sent by his staff. But it stopped being true in March 2017, when Trump switched to using an iPhone.

Let’s dive into at the history of all the devices used to tweet from the account, since the first tweets in 2009.

library(forcats)

all_tweets %>%

mutate(source = fct_lump(source, 5)) %>%

count(month = round_date(created_at, "month"), source) %>%

complete(month, source, fill = list(n = 0)) %>%

mutate(source = reorder(source, -n, sum)) %>%

group_by(month) %>%

mutate(percent = n / sum(n),

maximum = cumsum(percent),

minimum = lag(maximum, 1, 0)) %>%

ggplot(aes(month, ymin = minimum, ymax = maximum, fill = source)) +

geom_ribbon() +

scale_y_continuous(labels = percent_format()) +

labs(x = "Time",

y = "% of Trump's tweets",

fill = "Source",

title = "Source of @realDonaldTrump tweets over time",

subtitle = "Summarized by month")

A number of different people have clearly tweeted for the \@realDonaldTrump account over time, forming a sort of geological strata. I’d divide it into basically five acts:

- Early days: All of Trump’s tweets until late 2011 came from the Web Client.

- Other platforms: There was then a burst of tweets from TweetDeck and TwitLonger Beta, but these disappeared. Some exploration (shown later) indicate these may have been used by publicists promoting his book, though some (like this one from TweetDeck) clearly either came from him or were dictated.

- Starting the Android: Trump’s first tweet from the Android was in February 2013, and it quickly became his main device.

- Campaign: The iPhone was introduced only when Trump announced his campaign by 2015. It was clearly used by one or more of his staff, because by the end of the campaign it made up a majority of the tweets coming from the account. (There was also an iPad used occasionally, which was lumped with several other platforms into the “Other” category). The iPhone reduced its activity after the election and before the inauguration.

- Trump’s switch to iPhone: Trump’s last Android tweet was on March 25th, 2017, and a few days later Trump’s staff confirmed he’d switched to using an iPhone.

Which devices did Trump use himself, and which did other people use to tweet for him? To answer this, we could consider that Trump almost never uses hashtags, pictures or links in his tweets. Thus, the percentage of tweets containing one of those features is a proxy for how much others are tweeting for him.

library(stringr)

all_tweets %>%

mutate(source = fct_lump(source, 5)) %>%

filter(!str_detect(text, "^(\"|RT)")) %>%

group_by(source, year = year(created_at)) %>%

summarize(tweets = n(),

hashtag = sum(str_detect(str_to_lower(text), "#[a-z]|http"))) %>%

ungroup() %>%

mutate(source = reorder(source, -tweets, sum)) %>%

filter(tweets >= 20) %>%

ggplot(aes(year, hashtag / tweets, color = source)) +

geom_line() +

geom_point() +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = seq(2009, 2017, 2)) +

scale_y_continuous(labels = percent_format()) +

facet_wrap(~ source) +

labs(x = "Time",

y = "% of Trump's tweets with a hashtag, picture or link",

title = "Tweets with a hashtag, picture or link by device",

subtitle = "Not including retweets; only years with at least 20 tweets from a device.")

This suggests that each of the devices may have a mix (TwitLonger Beta was certainly entirely staff, as was the mix of “Other” platforms during the campaign), but that only Trump ever tweeted from an Android.

When did Trump start talking about Barack Obama?

Now that we have data going back to 2009, we can take a look at how Trump used to tweet, and when his interest turned political.

In the early days of the account, it was pretty clear that a publicist was writing Trump’s tweets for him. In fact, his first-ever tweet refers to him in the third person:

The first hundred or so tweets follow a similar pattern (interspersed with a few cases where he tweets for himself and signs it). But this changed alongside his views of the Obama administration. Trump’s first-ever mention of Obama was entirely benign:

But his next were a different story. This article shows how Trump’s opinion of the administration turned from praise to criticism at the end of 2010 and in early 2011 when he started spreading a conspiracy theory about Obama’s country of origin. His second and third tweets about the president both came in July 2011, followed by many more.

What changed? Well, it was two months after the infamous 2011 White House Correspondents Dinner, where Obama mocked Trump for his conspiracy theories, causing Trump to leave in a rage. Trump has denied that the dinner pushed him towards politics… but there certainly was a reaction at the time.

all_tweets %>%

filter(!str_detect(text, "^(\"|RT)")) %>%

group_by(month = round_date(created_at, "month")) %>%

summarize(tweets = n(),

hashtag = sum(str_detect(str_to_lower(text), "obama")),

percent = hashtag / tweets) %>%

ungroup() %>%

filter(tweets >= 10) %>%

ggplot(aes(as.Date(month), percent)) +

geom_line() +

geom_point() +

geom_vline(xintercept = as.integer(as.Date("2011-04-30")), color = "red", lty = 2) +

geom_vline(xintercept = as.integer(as.Date("2012-11-06")), color = "blue", lty = 2) +

scale_y_continuous(labels = percent_format()) +

labs(x = "Time",

y = "% of Trump's tweets that mention Obama",

subtitle = paste0("Summarized by month; only months containing at least 10 tweets.\n",

"Red line is White House Correspondent's Dinner, blue is 2012 election."),

title = "Trump's tweets mentioning Obama")

between <- all_tweets %>%

filter(created_at >= "2011-04-30", created_at < "2012-11-07") %>%

mutate(obama = str_detect(str_to_lower(text), "obama"))

percent_mentioned <- mean(between$obama)Between July 2011 and November 2012 (Obama’s re-election), a full 32.3%% of Trump’s tweets mentioned Obama by name (and that’s not counting the ones that mentioned him or the election implicitly, like this). Of course, this is old news, but it’s an interesting insight into what Trump’s Twitter was up to when it didn’t draw as much attention as it does now.

Trump’s opinion of Obama is well known enough that this may be the most redundant sentiment analysis I’ve ever done, but it’s worth noting that this was the time period where Trump’s tweets first turned negative. This requires tokenizing the tweets into words. I do so with the tidytext package created by me and Julia Silge.

library(tidytext)

all_tweet_words <- all_tweets %>%

mutate(text = str_replace_all(text, "https?://t.co/[A-Za-z\\d]+|&", "")) %>%

filter(!str_detect(text, "^(\"|RT)")) %>%

unnest_tokens(word, text, token = "regex", pattern = reg) %>%

filter(!word %in% stop_words$word, str_detect(word, "[a-z]"))all_tweet_words %>%

inner_join(get_sentiments("afinn")) %>%

group_by(month = round_date(created_at, "month")) %>%

summarize(average_sentiment = mean(score), words = n()) %>%

filter(words >= 10) %>%

ggplot(aes(month, average_sentiment)) +

geom_line() +

geom_hline(color = "red", lty = 2, yintercept = 0) +

labs(x = "Time",

y = "Average AFINN sentiment score",

title = "@realDonaldTrump sentiment over time",

subtitle = "Dashed line represents a 'neutral' sentiment average. Only months with at least 10 words present in the AFINN lexicon")

(Did I mention you can learn more about using R for sentiment analysis in our new book?)

Changes in words since the election

My original analysis was on tweets in early 2016, and I’ve often been asked how and if Trump’s tweeting habits have changed since the election. The remainder of the analyses will look only at tweets since Trump launched his campaign (June 16, 2015), and disregards retweets.

library(stringr)

campaign_tweets <- all_tweets %>%

filter(created_at >= "2015-06-16") %>%

mutate(source = str_replace(source, "Twitter for ", "")) %>%

filter(!str_detect(text, "^(\"|RT)"))

tweet_words <- all_tweet_words %>%

filter(created_at >= "2015-06-16")We can compare words used before the election to ones used after.

ratios <- tweet_words %>%

mutate(phase = ifelse(created_at >= "2016-11-09", "after", "before")) %>%

count(word, phase) %>%

spread(phase, n, fill = 0) %>%

mutate(total = before + after) %>%

mutate_at(vars(before, after), funs((. + 1) / sum(. + 1))) %>%

mutate(ratio = after / before) %>%

arrange(desc(ratio))What words were used more before or after the election?

Some of the words used mostly before the election included “Hillary” and “Clinton” (along with “Crooked”), though he does still mention her. He no longer talks about his competitors in the primary, including (and the account no longer has need of the #trump2016 hashtag).

Of course, there’s one word with a far greater shift than others: “fake”, as in “fake news”. Trump started using the term only in January, claiming it after some articles had suggested fake news articles were partly to blame for Trump’s election.

As of early August Trump is using the phrase more than ever, with about 9% of his tweets mentioning it. As we’ll see in a moment, this was a savvy social media move.

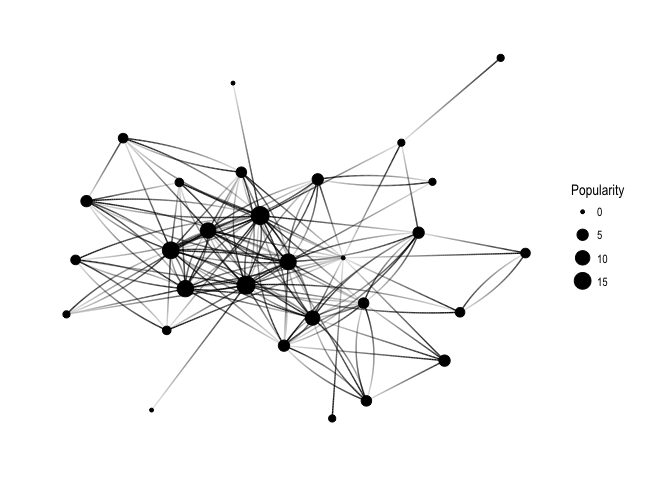

What words lead to retweets?

One of the most common follow-up questions I’ve gotten is what terms tend to lead to Trump’s engagement.

word_summary <- tweet_words %>%

group_by(word) %>%

summarize(total = n(),

median_retweets = median(retweet_count))What words tended to lead to unusually many retweets, or unusually few?

word_summary %>%

filter(total >= 25) %>%

arrange(desc(median_retweets)) %>%

slice(c(1:20, seq(n() - 19, n()))) %>%

mutate(type = rep(c("Most retweets", "Fewest retweets"), each = 20)) %>%

mutate(word = reorder(word, median_retweets)) %>%

ggplot(aes(word, median_retweets)) +

geom_col() +

labs(x = "",

y = "Median # of retweets for tweets containing this word",

title = "Words that led to many or few retweets") +

coord_flip() +

facet_wrap(~ type, ncol = 1, scales = "free_y")

Some of Trump’s most retweeted topics include Russia, North Korea, the FBI (often about Clinton), and, most notably, “fake news”.

Of course, Trump’s tweets have gotten more engagement over time as well (which partially confounds this analysis: worth looking into more!) His typical number of retweets skyrocketed when he announced his campaign, grew throughout, and peaked around his inauguration (though it’s stayed pretty high since).

all_tweets %>%

group_by(month = round_date(created_at, "month")) %>%

summarize(median_retweets = median(retweet_count), number = n()) %>%

filter(number >= 10) %>%

ggplot(aes(month, median_retweets)) +

geom_line() +

scale_y_continuous(labels = comma_format()) +

labs(x = "Time",

y = "Median # of retweets")

Also worth noticing: before the campaign, the only patch where he had a notable increase in retweets was his year of tweeting about Obama. Trump’s foray into politics has had many consequences, but it was certainly an effective social media strategy.

Conclusion: I wish this hadn’t aged well

Until today, last year’s Trump post was the only blog post that analyzed politics, and (not unrelatedly!) the highest amount of attention any of my posts have received. I got to write up an article for the Washington Post, and was interviewed on Sky News, CTV, and NPR. People have built great tools and analyses on top of my work, with some of my favorites including didtrumptweetit.com and the Atlantic’s analysis. And I got the chance to engage with, well, different points of view.

The post has certainly had some professional value. But it disappoints me that the analysis is as relevant as it is today. At the time I enjoyed my 15 minutes of fame, but I also hoped it would end. (“Hey, remember when that Twitter account seemed important?” “Can you imagine what Trump would tweet about this North Korea thing if we were president?”) But of course, Trump’s Twitter account is more relevant than ever.

I don’t love analysing political data; I prefer writing about baseball, biology, R education, and programming languages. But as you might imagine, that’s the least of the reasons I wish this particular chapter of my work had faded into obscurity.

About the author:

David Robinson is a Data Scientist at Stack Overflow. In May 2015, he received his PhD in Quantitative and Computational Biology from Princeton University, where he worked with Professor John Storey. His interests include statistics, data analysis, genomics, education, and programming in R.