Simpson (1951) demonstrated that a statistical relationship observed within a population—i.e., a group of individuals—could be reversed within all subgroups that make up that population. This phenomenon, where X seems to relate to Y in a certain way, but flips direction when the population is split for W, has since been referred to as Simpson’s paradox. Others names, according to Wikipedia, include the Simpson-Yule effect, reversal paradox or amalgamation paradox.

The most famous example has to be the seemingly gender-biased Berkeley admission rates:

“Examination of aggregate data on graduate admissions to the University of California, Berkeley, for fall 1973 shows a clear but misleading pattern of bias against female applicants. Examination of the disaggregated data reveals few decision-making units that show statistically significant departures from expected frequencies of female admissions, and about as many units appear to favor women as to favor men. If the data are properly pooled, taking into account the autonomy of departmental decision making, thus correcting for the tendency of women to apply to graduate departments that are more difficult for applicants of either sex to enter, there is a small but statistically significant bias in favor of women. […] The bias in the aggregated data stems not from any pattern of discrimination on the part of admissions committees, which seem quite fair on the whole, but apparently from prior screening at earlier levels of the educational system.” – part of abstract of Bickel, Hammel, & O’Connel (1975)

In a table, the effect becomes clear. While it seems as if women are rejected more often overall, women are actually less often rejected on a departmental level. Women simply applied to more selective departments more often (E & C below), resulting in the overall lower admission rate for women (35% as opposed to 44% for men).

Examples in HR

Simpsons Paradox can easily occur in organizational or human resources settings as well. Let me run you through two illustrated examples, I simulated:

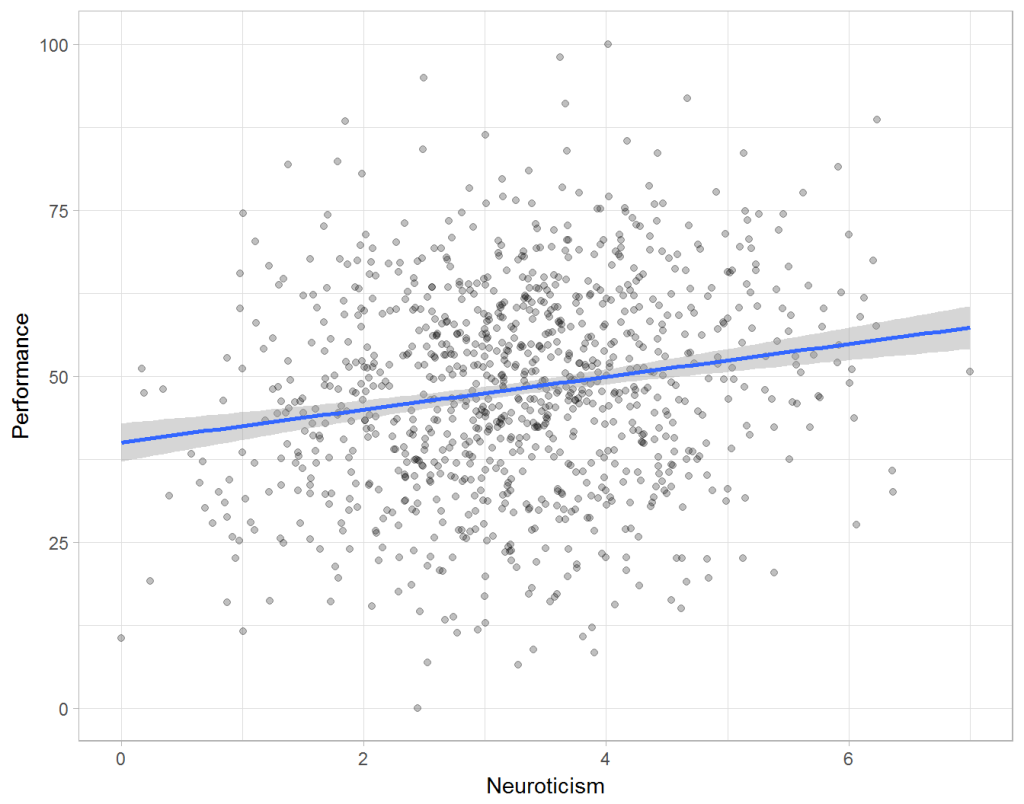

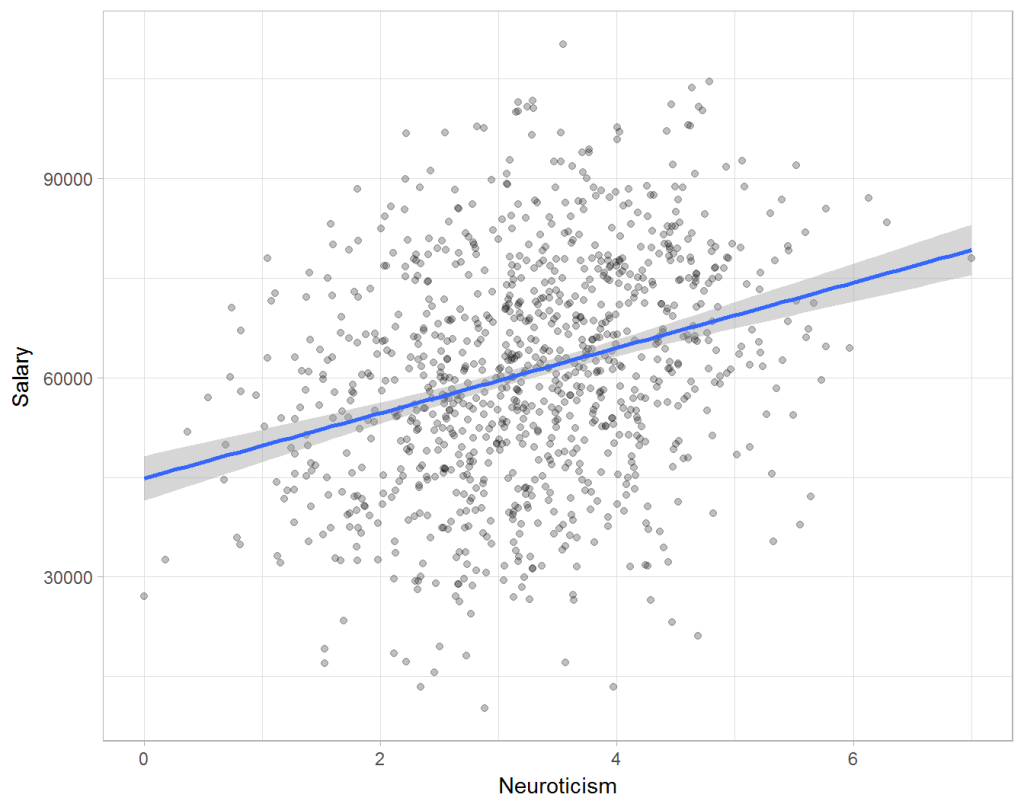

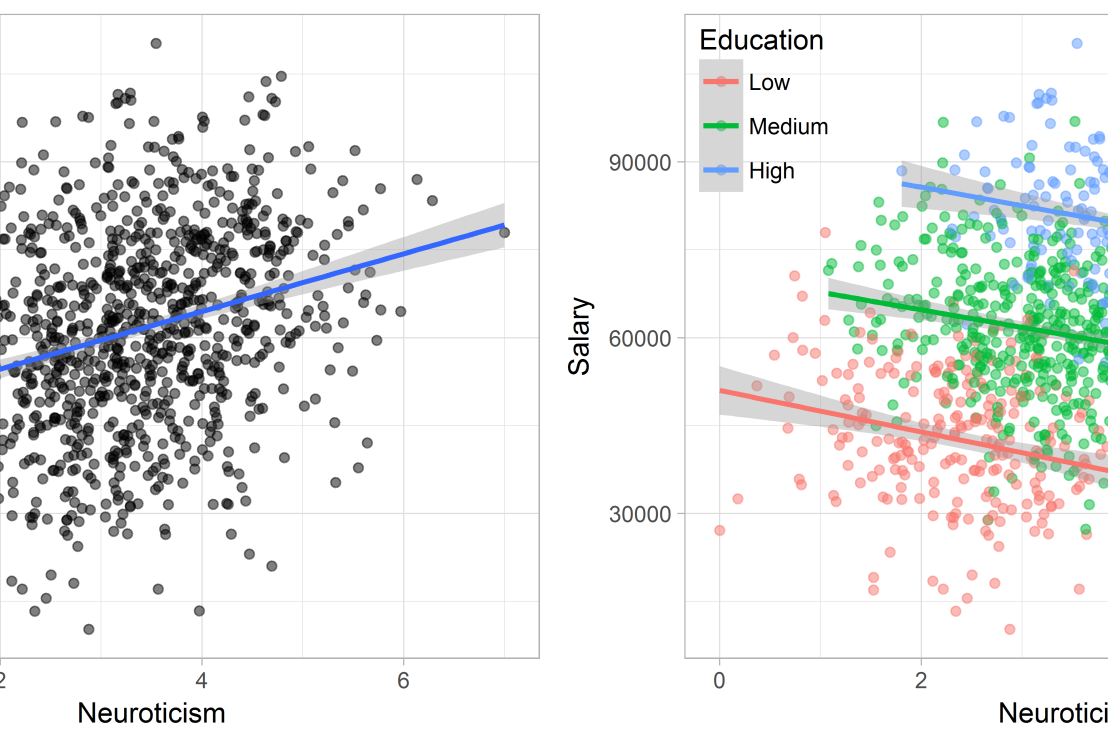

Assume you run a company of 1000 employees and you have asked all of them to fill out a Big Five personality survey. Per individual, you therefore have a score depicting his/her personality characteristic Neuroticism, which can run from 0 (not at all neurotic) to 7 (very neurotic). Now you are interested in the extent to which this Neuroticism of employees relates to their Job Performance (measured 0 – 100) and their Salary (measured in Euro’s per Year). In order to get a sense of the effects, you may decide to visualize both these relations in scatter plots:

From these visualizations it would look like Neuroticism relates significantly and positively to both employees’ performance and their yearly salary. Should you select more neurotic people to improve your overall company performance? Or are you discriminating emotionally-stable (non-neurotic) employees when it comes to salary?

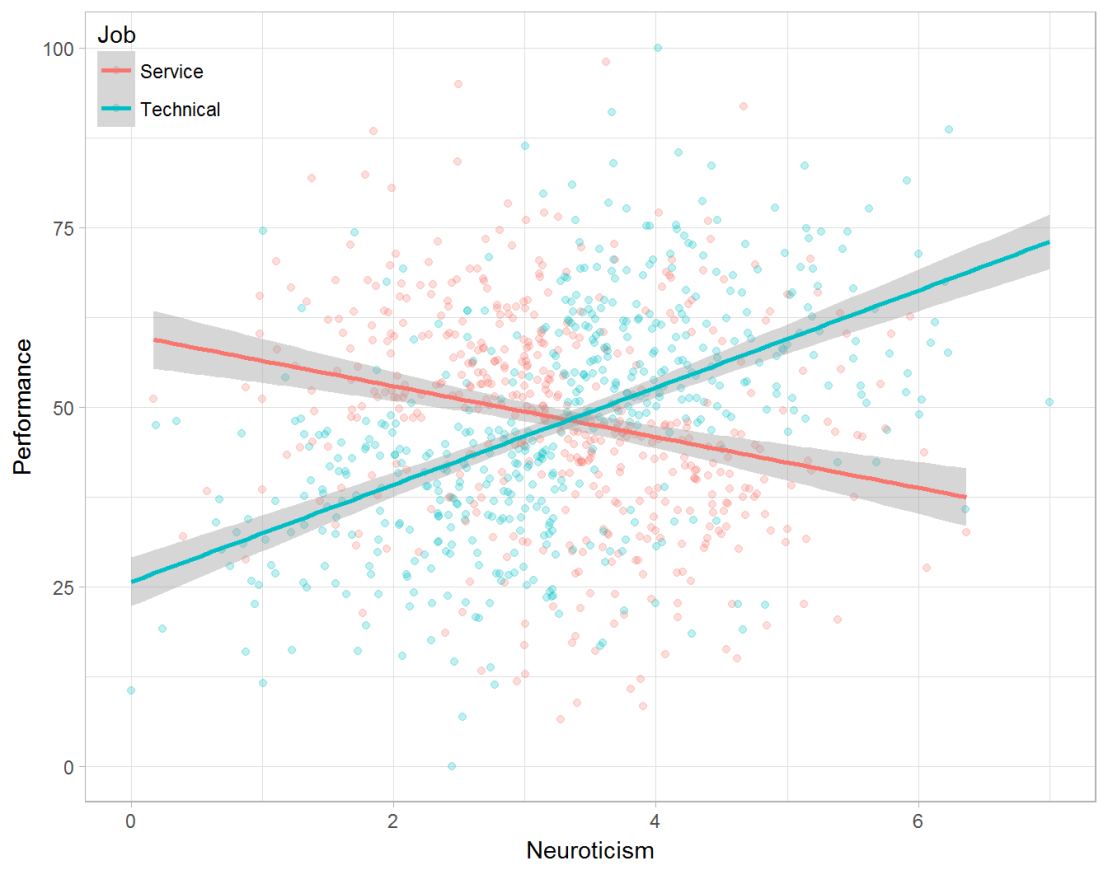

Taking a closer look at the subgroups in your data, you might however find very different relationships. For instance, the positive relationship between neuroticism and performance may only apply to technical positions, but not to those employees’ in service-oriented jobs.

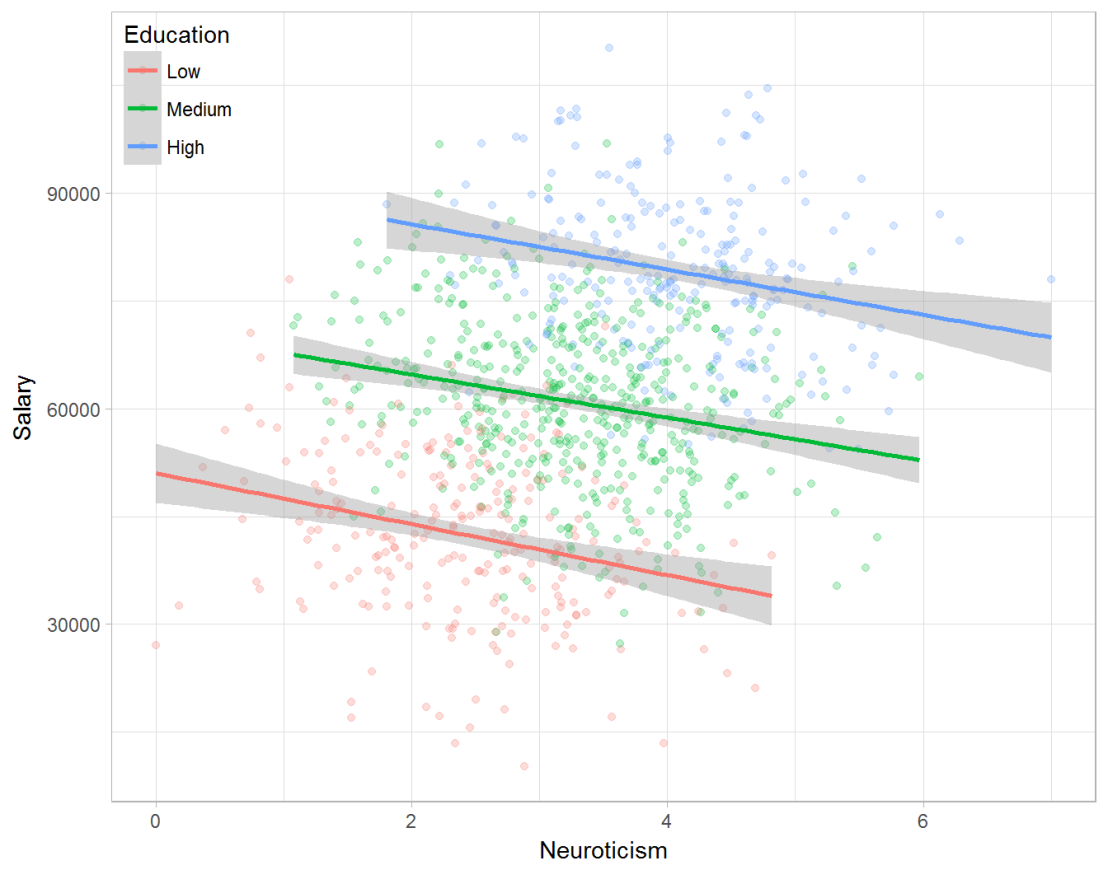

Similarly, splitting the employees by education level, it becomes clear that there is a relationship between neuroticism and education level that may explain the earlier association with salary. More educated employees receive higher salaries and within these groups, neuroticism is actually related to lower yearly income.

If you’d like to see the code used to simulate these data and generate the examples, you can find the R markdown file here on Rpubs.

Solving the paradox

Kievit and colleagues (2013) argue that Simpsons paradox may occur in a wide variety of research designs, methods, and questions, particularly within the social and medical sciences. As such, they propose several means to “control” or minimize the risk of it occurring. The paradox may be prevented from occurring altogether by more rigorous research design: testing mechanisms in longitudinal or intervention studies. However, this is not always feasible. Alternatively, the researchers pose that data visualization may help recognize the patterns and subgroups and thereby diagnose paradoxes. This may be easy if your data looks like this:

But rather hard, or even impossible, when your data looks more like the below:

Clustering may nevertheless help to detect Simpson’s paradox when it is not directly observable in the data. To this end, Kievit and Epskamp (2012) have developed a tool to facilitate the detection of hitherto undetected patterns of association in existing datasets. It is written in R, a language specifically tailored for a wide variety of statistical analyses which makes it very suitable for integration into the regular analysis workflow. As an R package, the tool is is freely available and specializes in the detection of cases of Simpson’s paradox for bivariate continuous data with categorical grouping variables (also known as Robinson’s paradox), a very common inference type for psychologists. Finally, its code is open source and can be extended and improved upon depending on the nature of the data being studied.

One example of application is provided in the paper, for a dataset on coffee and neuroticism. A regression analysis would suggest a significant positive association between coffee and neuroticism overall. However, when the detection algorithm of the R package is applied, a different picture appears: the analysis shows that there are three latent clusters present and that the purported positive relationship only holds for one cluster whereas it is negative in the others.

Update 24-10-2017: minutephysics – one of my favorite YouTube channels – uploaded a video explaining Simpson’s paradox very intuitively in a medical context:

Update 01-11-2017: minutephysics uploaded a follow-up video:

The paradox is that we remain reluctant to fight our bias, even when they are put in plain sight.

“[…] much of Uber’s communication with drivers over the years has aimed at combating shortages by advising drivers to move to areas where they exist, or where they might arise. Uber encouraged its local managers to experiment with ways of achieving this.[…] Some local managers who were men went so far as to adopt a female persona for texting drivers, having found that the uptake was higher when they did.”

“[…] much of Uber’s communication with drivers over the years has aimed at combating shortages by advising drivers to move to areas where they exist, or where they might arise. Uber encouraged its local managers to experiment with ways of achieving this.[…] Some local managers who were men went so far as to adopt a female persona for texting drivers, having found that the uptake was higher when they did.” “For months, when drivers tried to log out, the app would frequently tell them they were only a certain amount away from making a seemingly arbitrary sum for the day, or from matching their earnings from that point one week earlier.The messages were intended to exploit another relatively widespread behavioral tic — people’s preoccupation with goals — to nudge them into driving longer. […] Are you sure you want to go offline?” Below were two prompts: “Go offline” and “Keep driving.” The latter was already highlighted.”

“For months, when drivers tried to log out, the app would frequently tell them they were only a certain amount away from making a seemingly arbitrary sum for the day, or from matching their earnings from that point one week earlier.The messages were intended to exploit another relatively widespread behavioral tic — people’s preoccupation with goals — to nudge them into driving longer. […] Are you sure you want to go offline?” Below were two prompts: “Go offline” and “Keep driving.” The latter was already highlighted.”