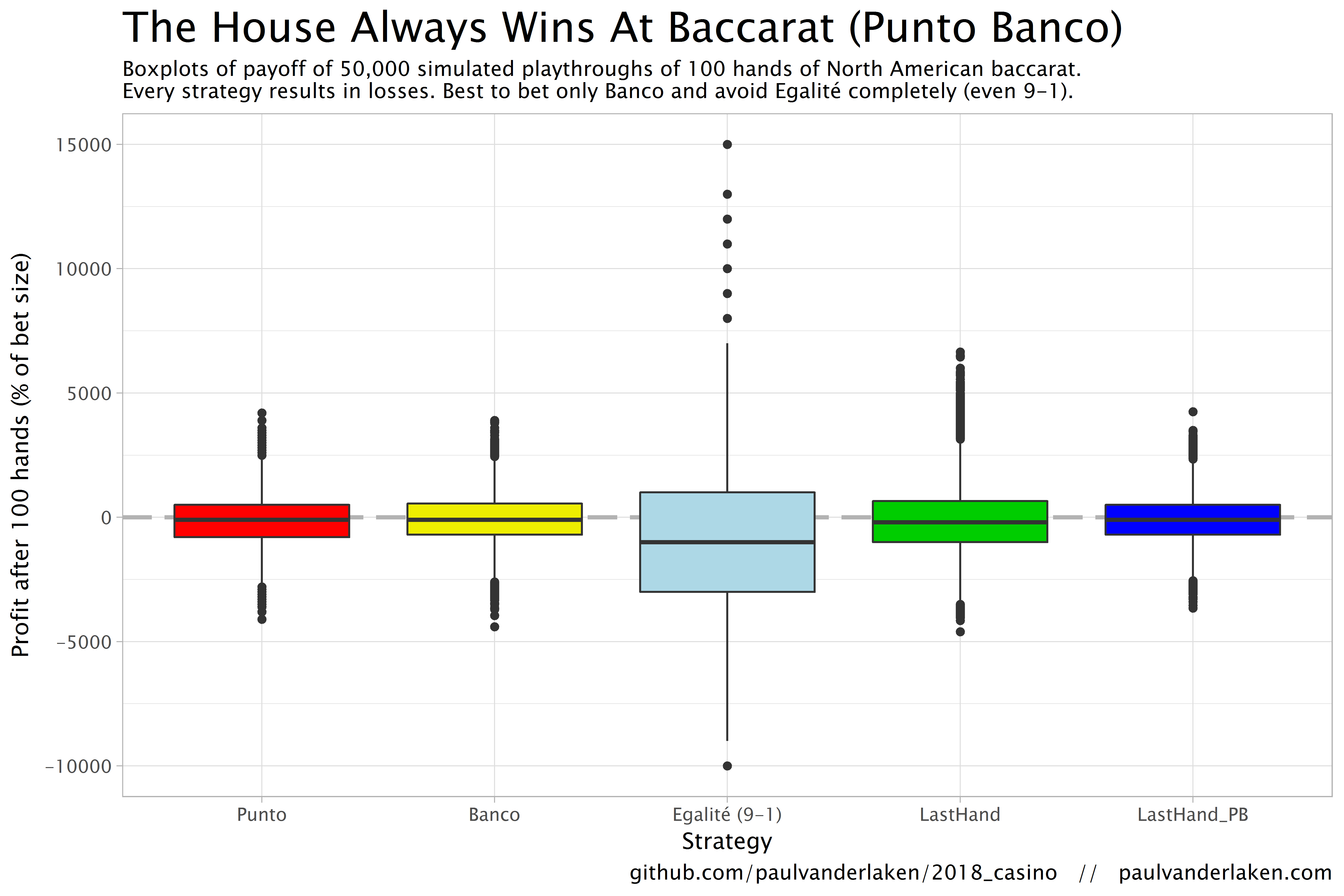

There has been a lot of hype around data the past years. With the big data buzz cooling down, data now needs to be smart, apparently. Data scientists became the most sexy professionals alive, and got a martial arts assistant. Artificial intelligence has been hot for decades, the term seems to change meaning every now and then. Currently, machine and deep learning are the quickest rising data domains.

Things can get confusing quite quickly if you’re a layman. People boast about boosting while deep, brain-like networks are used to play child’s games. Data guru’s speak of mighty, though random woodlands and the media simultaneously praise and criticize IBM Watson. To create even more confusion, consultancy firms introduce a new type of analytics every year, each one more valuable than its predecessor. I am not even kidding, I counted seven eight nine ten eleven types: descriptive, diagnostic, exploratory, inferential, strategic, causal, enterprise, advanced, predictive, prescriptive, adaptive, and cognitive analytics, roughly in that order of complexity.

The resulting confusion I experience firsthand in my work. In my workshops, people would ask questions like “How can I use data mining to make our dashboards to more predictive?” or “How can I build neural networks to understand our customer needs?”. Similarly, I’ve heard managers ask for more “cognitive solutions” or “one of those fancy neural networks“. However, things can get pretty ugly, pretty soon, once unnecessary complexity is introduced without good reasons (e.g., superior performance, processing speed), appropriate foundations (e.g., accurate, valid, and sufficient data), or good research designs (e.g., control conditions, random assignment, out-of-sample validation).

It is high time to demystify the data domain. If people outside the direct domain know what’s what, they will better understand what can and can’t be done with data. Moreover, they will not be as easily fooled by the cognitive AI mumbojumbo of consultants. A recent blog made me very happy. David Robinson — data scientist at StackOverflow — proposes very simple definitions of three interrelated domains (data science, machine learning, and artificial intelligence) and highlights their differences. If you haven’t yet, do read it, but to summarize David’s take:

- Data science produces insights

- Machine learning produces predictions

- Artificial intelligence produces actions

These definitions are overly simplistic, David acknowledges, and not without their flaws: “A fortune teller makes predictions, but we’d never say that they’re doing machine learning!”. However, I feel its a great first attempt at demystification. Particularly, the applied example with which David continues make matters more clear:

Suppose we were building a self-driving car, and were working on the specific problem of stopping at stop signs. We would need skills drawn from all three of these fields.

- Machine learning: The car has to recognize a stop sign using its cameras. We construct a dataset of millions of photos of streetside objects, and train an algorithm to predict which have stop signs in them.

- Artificial intelligence: Once our car can recognize stop signs, it needs to decide when to take the action of applying the brakes. It’s dangerous to apply them too early or too late, and we need it to handle varying road conditions (for example, to recognize on a slippery road that it’s not slowing down quickly enough), which is a problem of control theory.

- Data science: In street tests, we find that the car’s performance isn’t good enough, with some false negatives in which it drives right by a stop sign. After analyzing the street test data, we gain the insight that the rate of false negatives depends on the time of day: it’s more likely to miss a stop sign before sunrise or after sunset. We realize that most of our training data included only objects in full daylight, so we construct a better dataset including nighttime images and go back to the machine learning step.

David Robinson (2017; source)

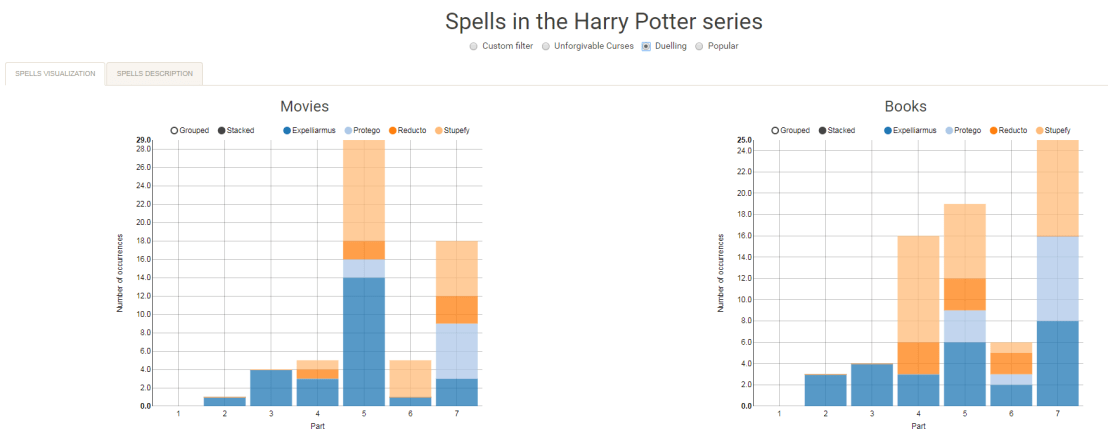

Around the same time I read David’s blog, I came across the picture below, and its brother:

This got me thinking about how I would explain the field to a layman. In Human Resource Management (my PhD domain), there is enormous confusion around what’s what. When HR professionals speak of analytics they can mean about anything from a group average or a bar chart up to a deep neural network. I hoped that a simple diagram could help solve some of the confusion in terminology. Here’s my attempt:

Note that this diagram reflects my personal, implicit definitions of the concepts. Hence, in many ways, it may be biased, incorrect, or plain stupid. Fortunately, the r/datascience and r/MachineLearning communities were very willing to help me improve it. I should also stress that David’s blog inspired the attempt in the first place. While the diagram still greatly oversimplifies matters (and is in conflict with the purist academic definitions), I hope its helps as a layman’s introduction to the field.

- How to read it? From left to right, we start out with raw data. Often, we’d first transform this data into usable features/variables: discriminatory characteristics of the objects were trying to analyze. On the one hand, a researcher may engineer these features. For instance, by some (statistical) transformation such as taking the average X within groups or reducing the number of categories for Z. On the other hand, unsupervised machine learning techniques may be applied to (semi-)automatically engineer features by identifying relevant clusters or dimensions in the data.

Next, the features can be input into statistical analysis. Taking the upper path, both unsupervised and supervised machine learning techniques can be used to build models that can be interpreted to gain insights about phenomena. This process is what business people usually mean when they say “analytics“. Mostly, it involves descriptive, causal or inferential analyses in order to gain insights into some process or phenomenon. Taking the lower path, supervised learning may be applied build a predictive model and retrieve predictions for a dependent variable. These predictions may also be evaluated using further analysis to retrieve insights. For instance, to gain understanding about what’s driving the predictions or how the predictions may be leveraged in practice.

Finally, both predictions and insights may form the basis of actions, which can be taken by a human agent or by a computer agent. In the latter case, we would deal with AI by some definitions.

There is one more route in the diagram, going directly from the raw data to the predictions: deep learning. Here, a neural network may take in complex data (e.g., text, images, sound) and engineer relevant features autonomously to base predictions on. - Disclaimer: The diagram is a major oversimplification! Particularly the placement of and overlap between the domains in this diagram is a simplification and not very good by purist, academic standards. For instance, despite being a extremely important field of innovation, I excluded reinforcement learning as I was unable to place it without making the figure considerably more complex. Similarly, the others domains do not have as clear demarcations as this figure suggests and their placement is by my definition of them. Data science, in my opinion, reflects the diffusion of insights or knowledge from data, particularly the (human) decisions and actions made in that process. Much of data science relies on machine learning, which involves how algorithms learn a model of reality from data, observations, or experiences. This learning can occur in different forms (e.g., supervised, unsupervised, deep, and reinforcement learning) and, unlike David’s definition, thus not always output predictions (e.g., also dimensions, clusters). Finally, machine learning is a specific branch of artificial intelligence, a label that has had many definitions. In my eyes, it includes any (partially) automated process where seemingly intelligent actions are automatically executed based on decision rules. An action can be as simple as a single if-then statement or as complex as a smart fridge ordering new milk. Whether AI is or should be considered a part of data science is food for a different discussion. For much more straightforward definitions of the fields, please consult this slide shared by u/mmcmtl:

Definitions shared by u/mmcmtl in the reddit discussion.

If you have any thoughts on how the above diagram and/or blog could or should be improved, feel free to comment below, reach out, or share your own attempts!