Nicolas Rougier, Michael Droettboom, Philip Bourne wrote an open access article for the Public Library of Open Science (PLOS) in 2014, proposing ten simple rules for better figures. Below I posted these 10 rules and quote several main sentences extracted from the original article.

Rule 1: Know Your Audience

It is important to identify, as early as possible in the design process, the audience and the message the visual is to convey. The graphical design of the visual should be informed by this intent. […] The general public may be the most difficult audience of all since you need to design a simple, possibly approximated, figure that reveals only the most salient part of your research.

Rule 2: Identify Your Message

It is important to clearly identify the role of the figure, i.e., what is the underlying message and how can a figure best express this message? […] Only after identifying the message will it be worth the time to develop your figure, just as you would take the time to craft your words and sentences when writing an article only after deciding on the main points of the text.

Rule 3: Adapt the Figure to the Support Medium

Ideally, each type of support medium requires a different figure, and you should abandon the practice of extracting a figure from your article to be put, as is, in your oral presentation. […] For example, during an oral presentation, a figure will be displayed for a limited time. Thus, the viewer must quickly understand what is displayed and what it represents while still listening to your explanation.

Rule 4: Captions Are Not Optional

The caption explains how to read the figure and provides additional precision for what cannot be graphically represented. This can be thought of as the explanation you would give during an oral presentation, or in front of a poster, but with the difference that you must think in advance about the questions people would ask. […] if there is a point of interest in the figure (critical domain, specific point, etc.), make sure it is visually distinct but do not hesitate to point it out again in the caption.

Rule 5: Do Not Trust the Defaults

All plots require at least some manual tuning of the different settings to better express the message, be it for making a precise plot more salient to a broad audience, or to choose the best colormap for the nature of the data.

Rule 6: Use Color Effectively

As explained by Edward Tufte [1], color can be either your greatest ally or your worst enemy if not used properly. If you decide to use color, you should consider which colors to use and where to use them. […] However, if you have no such need, you need to ask yourself, “Is there any reason this plot is blue and not black?”

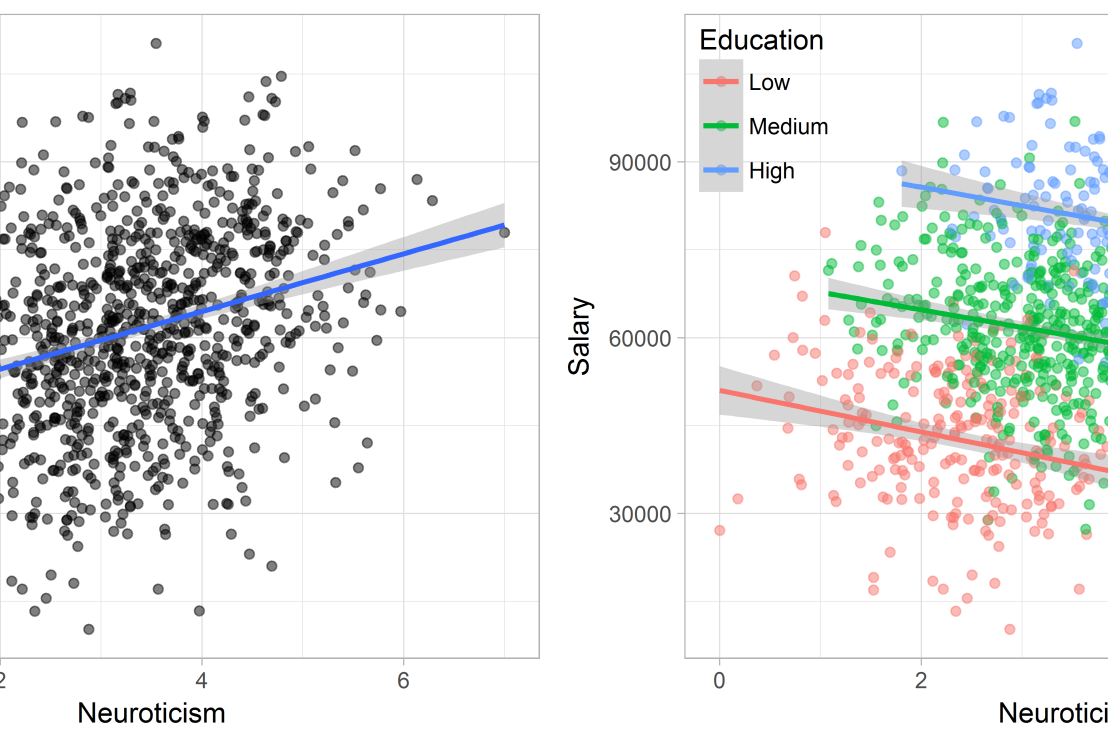

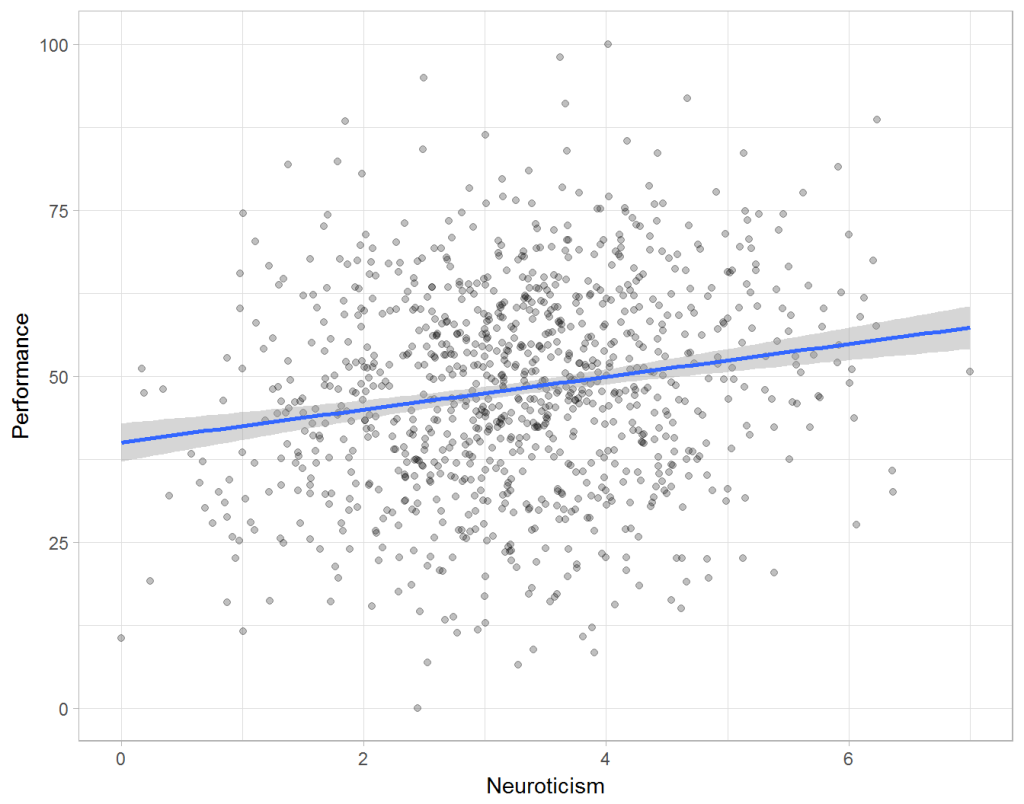

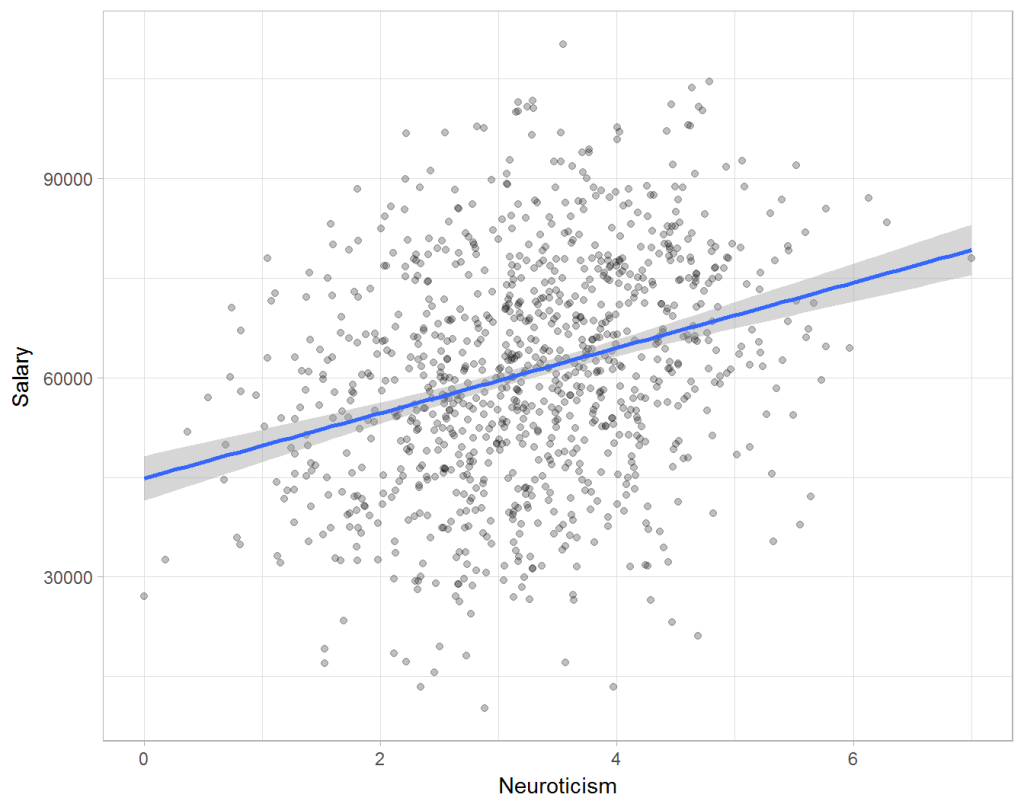

Rule 7: Do Not Mislead the Reader

What distinguishes a scientific figure from other graphical artwork is the presence of data that needs to be shown as objectively as possible. […] As a rule of thumb, make sure to always use the simplest type of plots that can convey your message and make sure to use labels, ticks, title, and the full range of values when relevant.

![journal.pcbi.1003833.g006[2].png](https://paulvanderlaken.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/journal-pcbi-1003833-g0062.png?w=1108)

Rule 8: Avoid “Chartjunk”

Chartjunk refers to all the unnecessary or confusing visual elements found in a figure that do not improve the message (in the best case) or add confusion (in the worst case). For example, chartjunk may include the use of too many colors, too many labels, gratuitously colored backgrounds, useless grid lines, etc. The term was first coined by Edward Tutfe [1]; he argues that any decorations that do not tell the viewer something new must be banned: “Regardless of the cause, it is all non-data-ink or redundant data-ink, and it is often chartjunk.” Thus, in order to avoid chartjunk, try to save ink, or electrons in the computing era.

Rule 9: Message Trumps Beauty

There exists a myriad of online graphics in which aesthetic is the first criterion and content comes in second place. Even if a lot of those graphics might be considered beautiful, most of them do not fit the scientific framework. Remember, in science, message and readability of the figure is the most important aspect while beauty is only an option.

Rule 10: Get the Right Tool

- Matplotlib is a python plotting library, primarily for 2-D plotting, but with some 3-D support, which produces publication-quality figures in a variety of hardcopy formats and interactive environments across platforms. It comes with a huge gallery of examples that cover virtually all scientific domains (http://matplotlib.org/gallery.html).

- R is a language and environment for statistical computing and graphics. R provides a wide variety of statistical (linear and nonlinear modeling, classical statistical tests, time-series analysis, classification, clustering, etc.) and graphical techniques, and is highly extensible.

- Inkscape is a professional vector graphics editor. It allows you to design complex figures and can be used, for example, to improve a script-generated figure or to read a PDF file in order to extract figures and transform them any way you like.

- TikZ and PGF are TeX packages for creating graphics programmatically. TikZ is built on top of PGF and allows you to create sophisticated graphics in a rather intuitive and easy manner, as shown by the Tikz gallery (http://www.texample.net/tikz/examples/all/).

- GIMP is the GNU Image Manipulation Program. It is an application for such tasks as photo retouching, image composition, and image authoring. If you need to quickly retouch an image or add some legends or labels, GIMP is the perfect tool.

- ImageMagick is a software suite to create, edit, compose, or convert bitmap images from the command line. It can be used to quickly convert an image into another format, and the huge script gallery (http://www.fmwconcepts.com/imagemagick/index.php) by Fred Weinhaus will provide virtually any effect you might want to achieve.

- D3.js (or just D3 for Data-Driven Documents) is a JavaScript library that offers an easy way to create and control interactive data-based graphical forms which run in web browsers, as shown in the gallery at http://github.com/mbostock/d3/wiki/Gallery.

- Cytoscape is a software platform for visualizing complex networks and integrating these with any type of attribute data. If your data or results are very complex, cytoscape may help you alleviate this complexity.

- Circos was originally designed for visualizing genomic data but can create figures from data in any field. Circos is useful if you have data that describes relationships or multilayered annotations of one or more scales.

You can download the PDF version of the full article here.

[1] Tufte EG (1983) The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. Cheshire, Connecticut: Graphics Press.