Cover image by xkcd

Over the last months I’ve been working my way through Project Euler in my spare time. I wanted to learn Python programming, and what better way than solving mini-problems and -projects?!

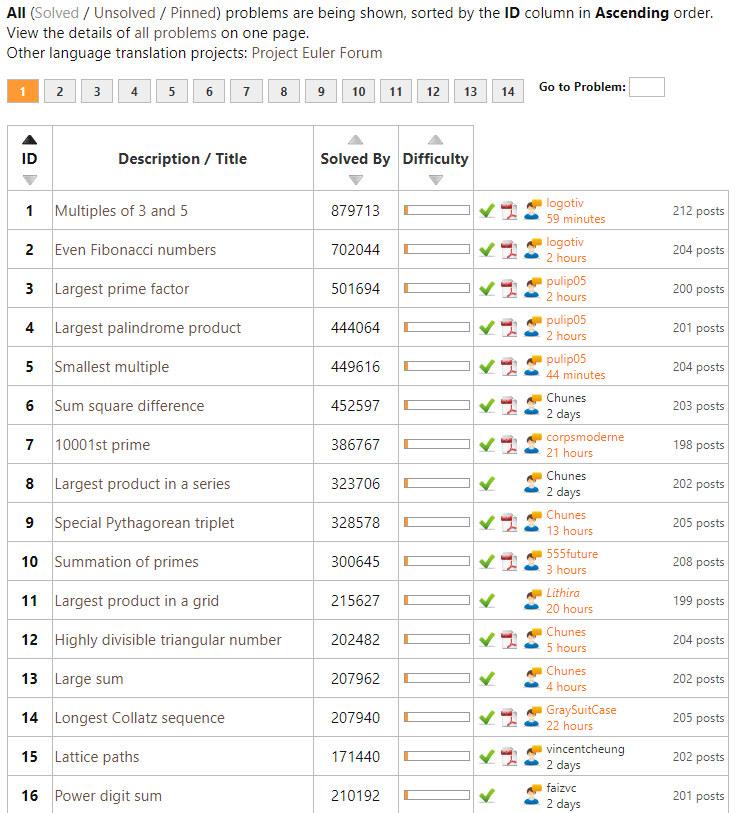

Well, Project Euler got a ton of these, listed in increasing order of difficulty. It starts out simple: to solve the first problem you need to write a program to identify multiples of 3 and 5. Next, in problem two, you are asked to sum the first thousand even Fibonacci numbers. Each problem, the task at hand gets slighly more difficult…

For me, Project Euler combines math, programming, and stats in a way that really keeps me motivated to continue and learn new concepts and programming / problem-solving approaches.

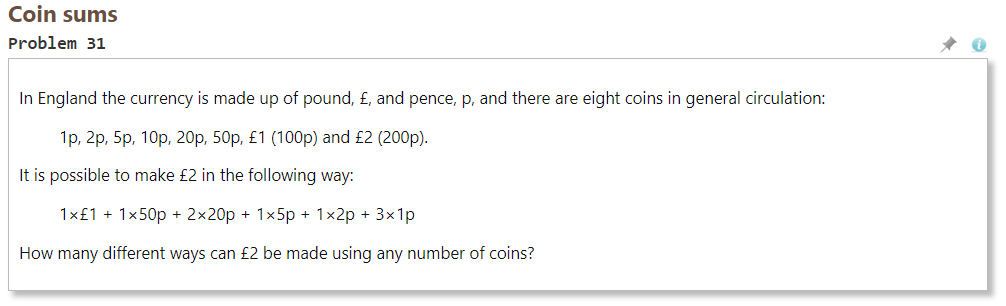

However, at problem 31, I really got stuck. For several hours, I struggled to solve it in a satisfactory fashion, even though most other problems only take 5-90 minutes.

After hours of struggling, I pretty much gave up, and googled some potential solutions. Aparently, the way to solve problem 31, is to take a so-called dynamic programming approach.

Dynamic programming is both a mathematical optimization method and a computer programming method. The method was developed by Richard Bellman in the 1950s and has found applications in numerous fields, from aerospace engineering to economics. In both contexts it refers to simplifying a complicated problem by breaking it down into simpler sub-problems in a recursive manner. While some decision problems cannot be taken apart this way, decisions that span several points in time do often break apart recursively. Likewise, in computer science, if a problem can be solved optimally by breaking it into sub-problems and then recursively finding the optimal solutions to the sub-problems, then it is said to have optimal substructure.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dynamic_programming

Now, this sounded like something I’d like to learn more about! I was already quite familiar with recursive problems and solutions, but this dynamic programming sounded next-level.

So I googled and googled for tutorials and other resources, and I finally came across this free 2011 MIT course that I intend to view over the coming weeks.

There’s even a course website with additional materials and assignments (in Python).

Will you join me? And let me know what you think!

For those less interested in (dynamic) programming but mostly in machine learning, there’s this other great MIT OpenCourseWare youtube playlist of their Artificial Intelligence course. I absolutely loved that course and I really powered through it in a matter of weeks (which is why I am already psyched about this new one). I learned so much new concepts, and I strongly recommend it. Unfortunately, the professor recently passed away.