GIFs or animations are rising quickly in the data visualization world (see for instance here).

However, in my personal experience, they are not as widely used in business settings. You might even say animations are frowned by, for instance, LinkedIn, which removed the option to even post GIFs on their platform!

Nevertheless, animations can be pretty useful sometimes. For instance, they can display what happens during a process, like a analytical model converging, which can be useful for didactic purposes. Alternatively, they can be great for showing or highlighting trends over time.

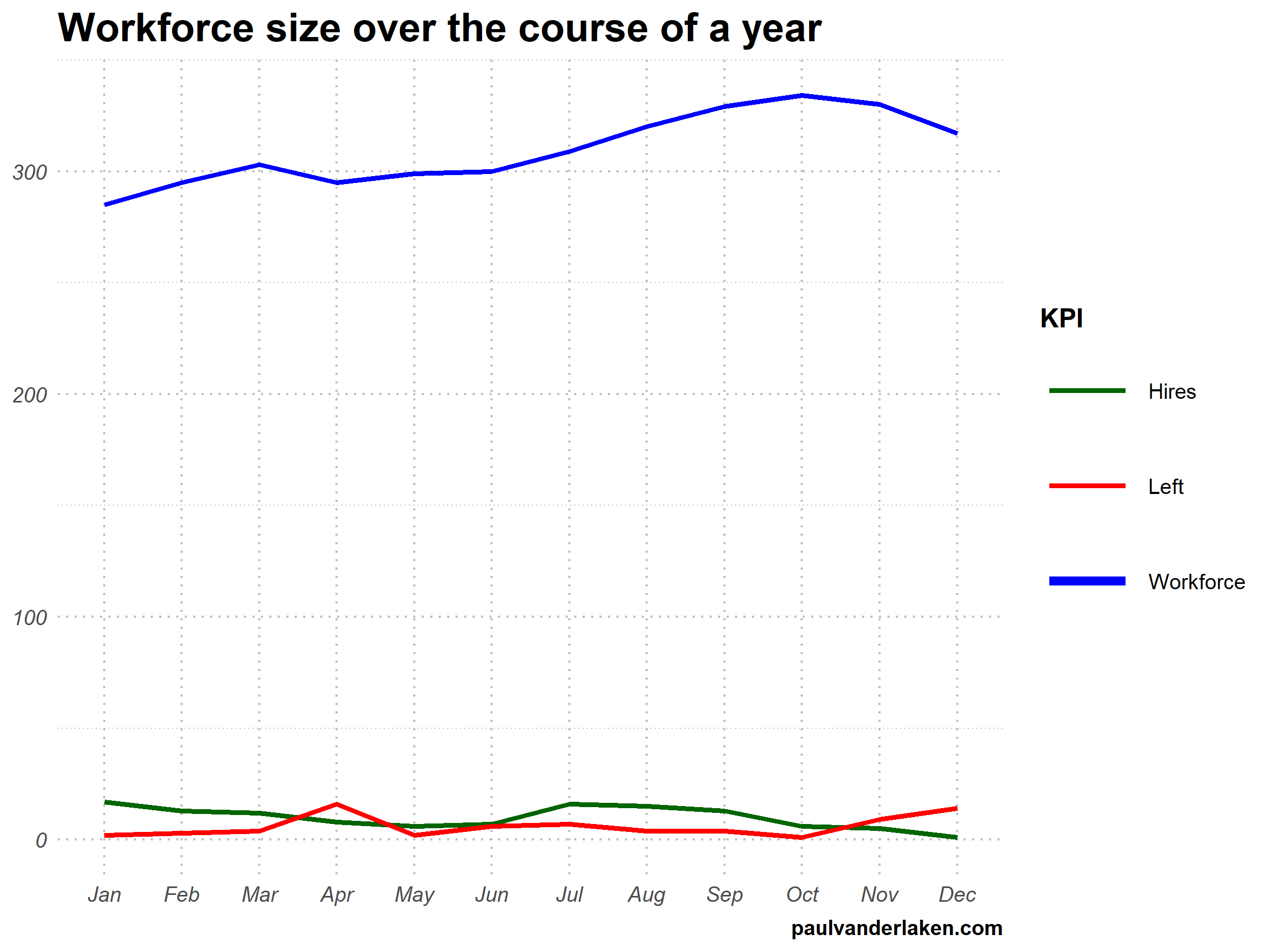

I am curious what you think are the pro’s and con’s of animations. Below, I posted two visualizations of the same data. The data consists of the simulated workforce trends, including new hires and employee attrition over the course of twelve months.

versus

Would you prefer the static, or the animated version? Please do share your thoughts in the comments below, or on the respective LinkedIn and Twitter posts!

Want to reproduce these plots? Or play with the data? Here’s the R code:

# LOAD IN PACKAGES ####

# install.packages('devtools')

# devtools::install_github('thomasp85/gganimate')

library(tidyverse)

library(gganimate)

library(here)

# SET CONSTANTS ####

# data

HEADCOUNT = 270

HIRE_RATE = 0.12

HIRE_ADDED_SEASONALITY = rep(floor(seq(14, 0, length.out = 6)), 2)

LEAVER_RATE = 0.16

LEAVER_ADDED_SEASONALITY = c(rep(0, 3), 10, rep(0, 6), 7, 12)

# plot

TEXT_SIZE = 12

LINE_SIZE1 = 2

LINE_SIZE2 = 1.1

COLORS = c("darkgreen", "red", "blue")

# saving

PLOT_WIDTH = 8

PLOT_HEIGHT = 6

FRAMES_PER_POINT = 5

# HELPER FUNCTIONS ####

capitalize_string = function(text_string){

paste0(toupper(substring(text_string, 1, 1)), substring(text_string, 2, nchar(text_string)))

}

# SIMULATE WORKFORCE DATA ####

set.seed(1)

# generate random leavers and some seasonality

leavers <- rbinom(length(month.abb), HEADCOUNT, TURNOVER_RATE / length(month.abb)) + LEAVER_ADDED_SEASONALITY

# generate random hires and some seasonality

joiners <- rbinom(length(month.abb), HEADCOUNT, HIRE_RATE / length(month.abb)) + HIRE_ADDED_SEASONALITY

# combine in dataframe

data.frame(

month = factor(month.abb, levels = month.abb, ordered = TRUE)

, workforce = HEADCOUNT - cumsum(leavers) + cumsum(joiners)

, left = leavers

, hires = joiners

) ->

wf

# transform to long format

wf_long <- gather(wf, key = "variable", value = "value", -month)

capitalize the name of variables

wf_long$variable <- capitalize_string(wf_long$variable)

# VISUALIZE & ANIMATE ####

# draw workforce plot

ggplot(wf_long, aes(x = month, y = value, group = variable)) +

geom_line(aes(col = variable, size = variable == "workforce")) +

scale_color_manual(values = COLORS) +

scale_size_manual(values = c(LINE_SIZE2, LINE_SIZE1), guide = FALSE) +

guides(color = guide_legend(override.aes = list(size = c(rep(LINE_SIZE2, 2), LINE_SIZE1)))) +

# theme_PVDL() +

labs(x = NULL, y = NULL, color = "KPI", caption = "paulvanderlaken.com") +

ggtitle("Workforce size over the course of a year") +

NULL ->

workforce_plot

# ggsave(here("workforce_plot.png"), workforce_plot, dpi = 300, width = PLOT_WIDTH, height = PLOT_HEIGHT)

# animate the plot

workforce_plot +

geom_segment(aes(xend = 12, yend = value), linetype = 2, colour = 'grey') +

geom_label(aes(x = 12.5, label = paste(variable, value), col = variable),

hjust = 0, size = 5) +

transition_reveal(variable, along = as.numeric(month)) +

enter_grow() +

coord_cartesian(clip = 'off') +

theme(

plot.margin = margin(5.5, 100, 11, 5.5)

, legend.position = "none"

) ->

animated_workforce

anim_save(here("workforce_animation.gif"),

animate(animated_workforce, nframes = nrow(wf) * FRAMES_PER_POINT,

width = PLOT_WIDTH, height = PLOT_HEIGHT, units = "in", res = 300))