I came across this PyData 2018 talk by Lucas Bernadi of Booking.com where he talks about the importance of selection bias for practical applications of machine learning.

We can’t just throw data into machines and expect to see any meaning […], we need to think [about this]. I see a strong trend in the practitioners community to just automate everything, to just throw data into a black box and expect to get money out of it, and I really don’t believe in that.

Lucas Bernadi in https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3ZWCKr0vDtc

All pictures below are slides from the above video.

My summary / interpretation

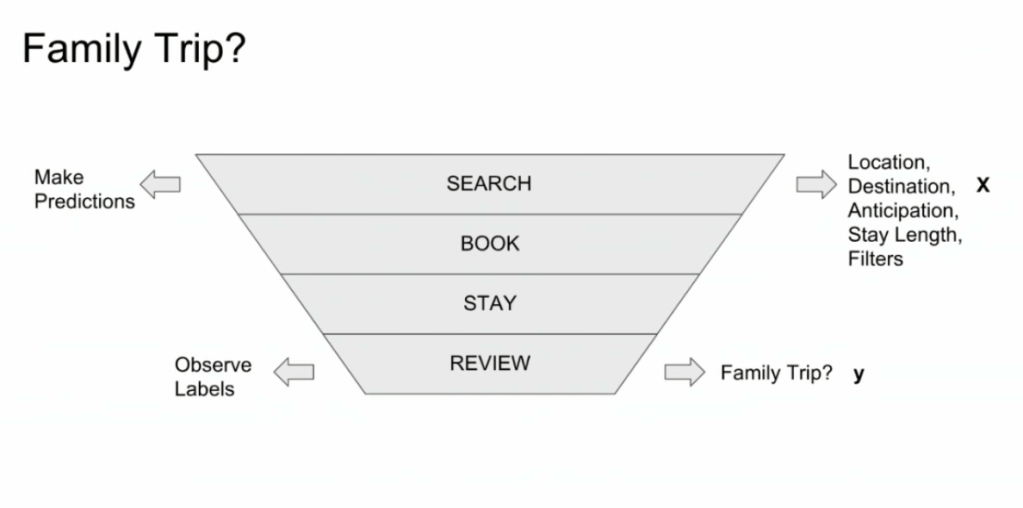

Lucas highlights an example he has been working on at Booking.com, where they seek to predict which searching activities on their website are for family trips.

What happens is that people forget to specify that they intend to travel as a family, forget to input one/two/three child travellers will come along on the trip, and end up not being able to book the accomodations that come up during their search. If Booking.com would know, in advance, that people (may) be searching for family accomodations, they can better guide these bookers to family arrangements.

The problem here is that many business processes in real life look and act like a funnel. Samples drop out of the process during the course of it. So too the user search activity on Booking.com’s website acts like a funnel.

- People come to search for arrangements

- Less people end up actually booking arrangements

- Even less people actually go on their trip

- And even less people then write up a review

However, only for those people that end up writing a review, Booking.com knows 100% certain that they it concerned a family trip, as that is the moment the user can specify so. Of all other people, who did not reach stage 4 of the funnel, Booking.com has no (or not as accurate an) idea whether they were looking for family trips.

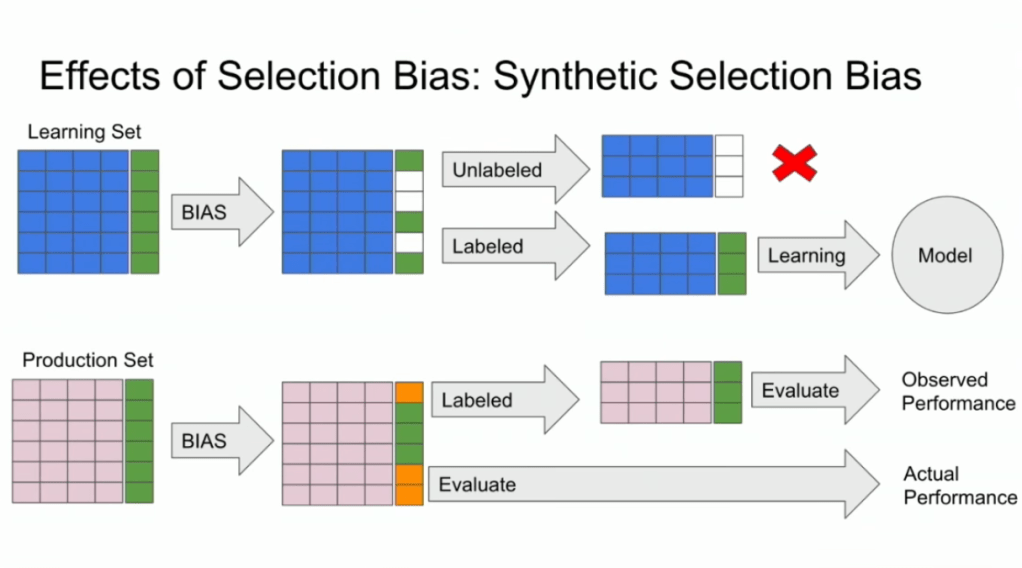

Such a funnel thus inherently produces business data with selection bias in it. Only for people making it to the review stage we know whether they were family trips or not. And only those labeled data can be used to train our machine learning model.

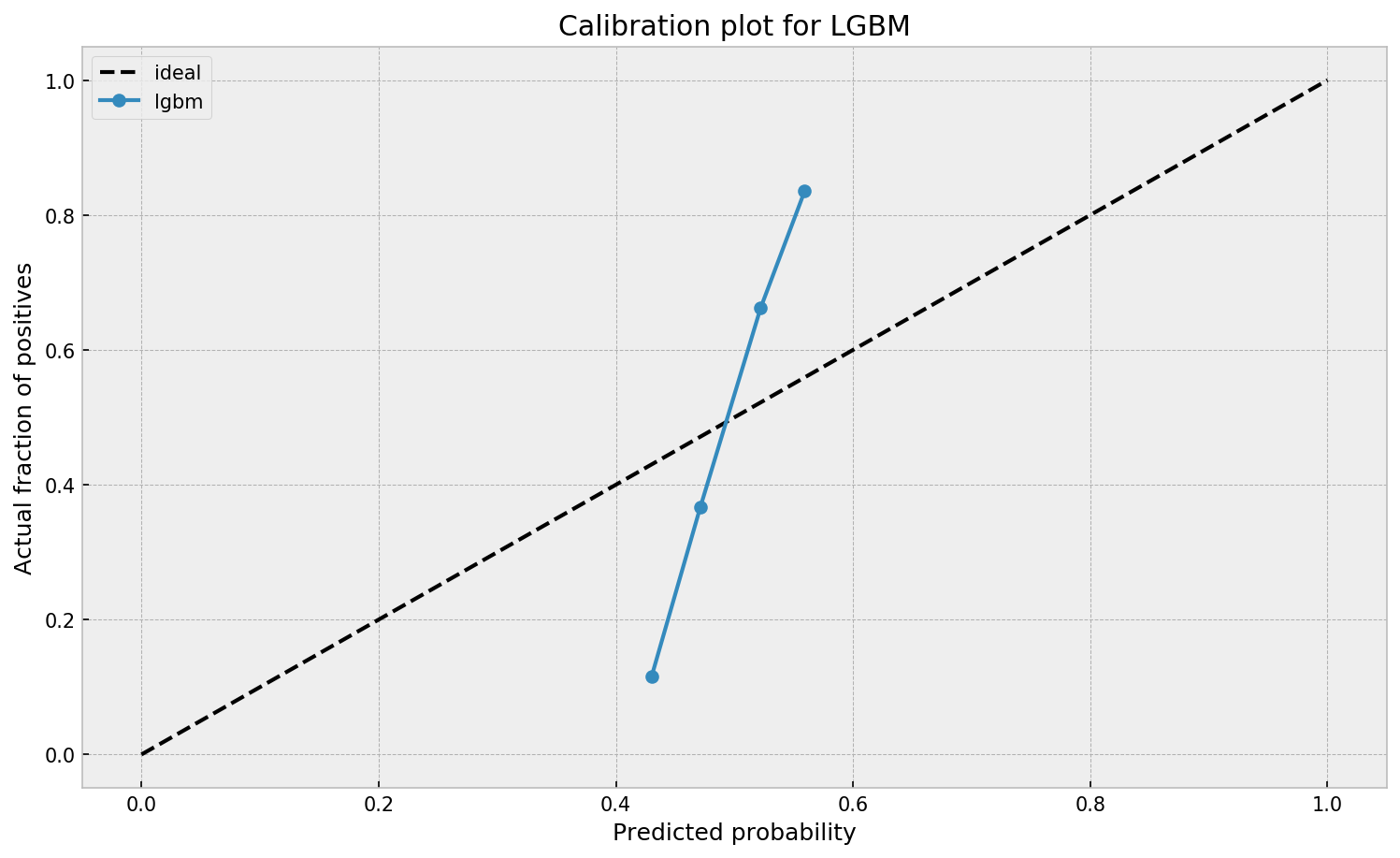

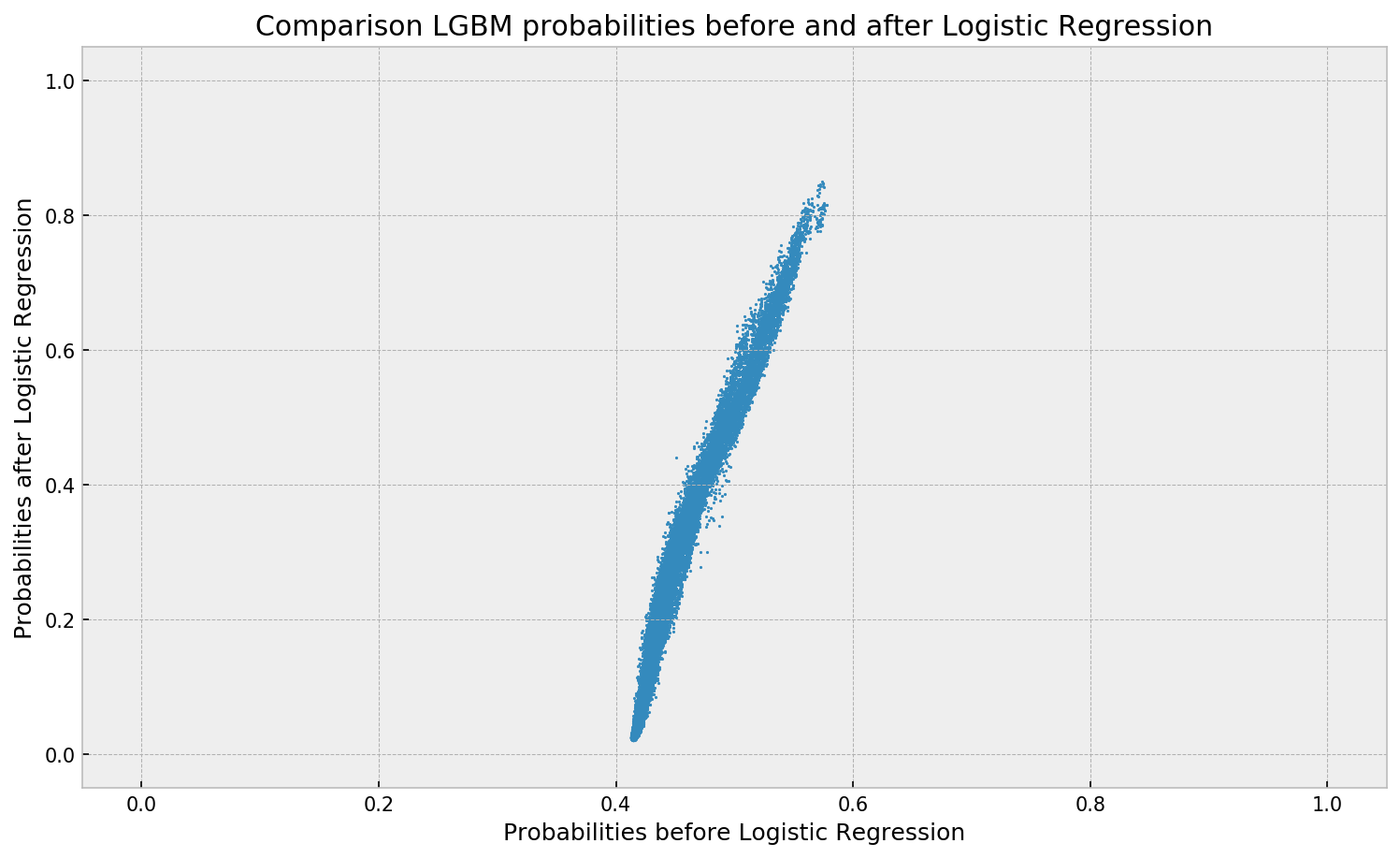

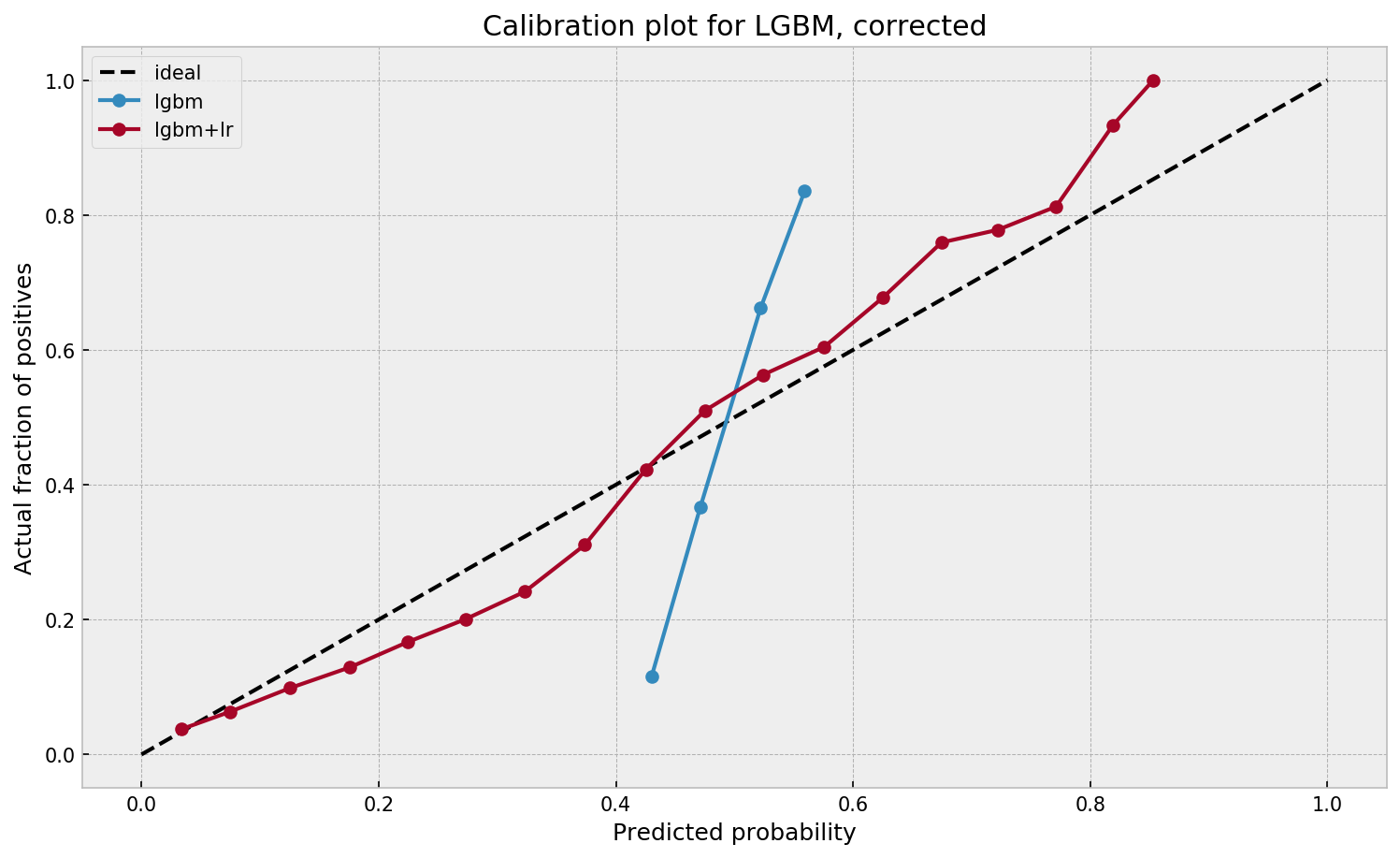

And now for the issue: if you train and evaluate a machine learning model on data generated with such a selection bias, your observed performance metrics will not reflect the actual performance of your machine learning model!

Actually, they are pretty much overestimates.

This is very much an issue, even though many ML practitioners don’t see aware. Selection bias makes us blind as to the real performance of our machine learning models. It produces high variance in the region of our feature space where labels are missing. This leads us to being overconfident in our ability to predict whether some user is looking for a family trip. And if the mechanism causing the selection bias is still there, we could never find out that we are overconfident. Consistently estimating, say, 30% of people are looking for family trips, whereas only 25% are.

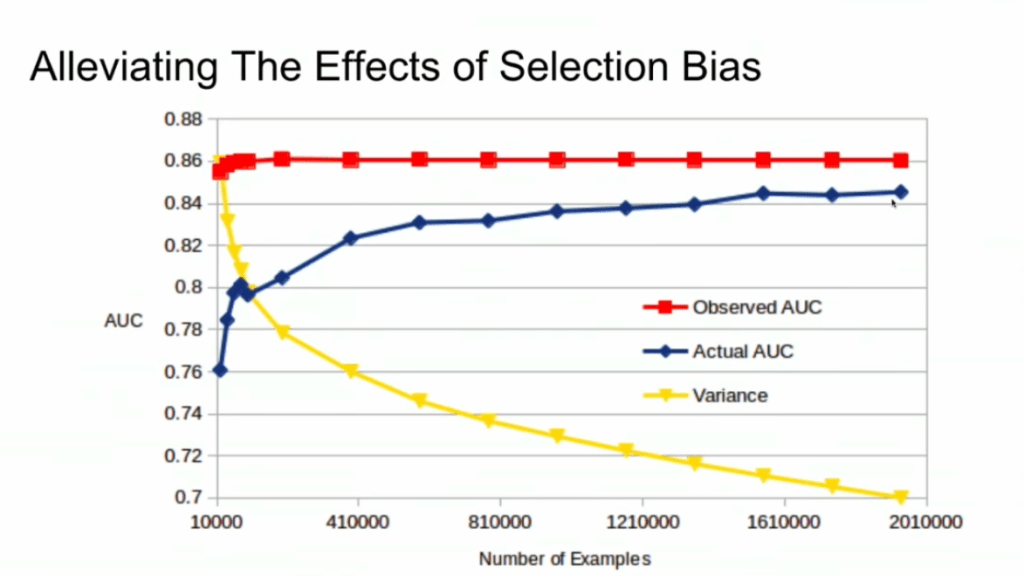

Fortunately, Lucas proposes a very simple solution! Just adding more observations can (partially) alleviate this detrimental effect of selection bias. Although our bias still remains, the variance goes down and the difference between our observed and actual performance decreases.

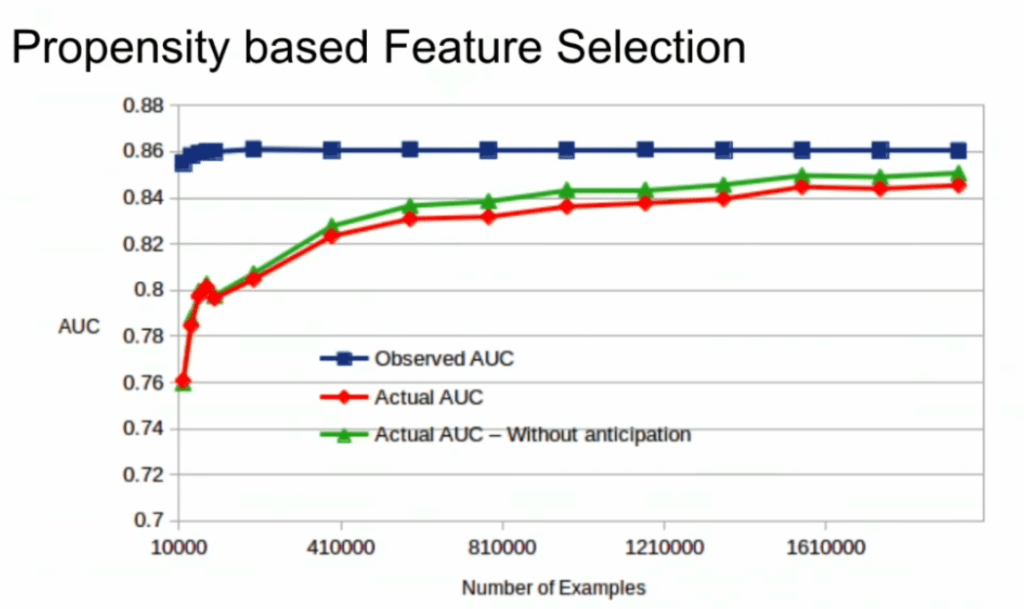

A second issue and solution to selection bias relates to propensity (see also): the extent to which your features X influence not only the outcome Y, but also the selection criteria s.

If our features X influence both the outcome Y but also the selection criteria s, selection bias will occur in your data and can thus screw up your conclusion. In order to inspect to what extent this occurs in your setting, you will want to estimate a propensity model. If that model is good, and X appears valuable in predicting s, you have a selection bias problem.

Via a propensity model s ~ X, we quantify to what extent selection bias influences our data and model. The nice thing is that we, as data scientists, control the features X we use to train a model. Hence, we could just use only features X that do not predict s to predict Y. Conclusion: we can conduct propensity-based feature selection in our Y ~ X by simply avoiding features X that predicted s!

Still, Lucas does point that this becomes difficult when you have valuable features that predict both s and Y. Hence, propensity-based feature selection may end up cost(ing) you performance, as you will need to remove features relevant to Y.

I am sure I explained this phenomena worse than Lucas did himself, so please do have a look at the original PyData 2018 Amsterdam video!