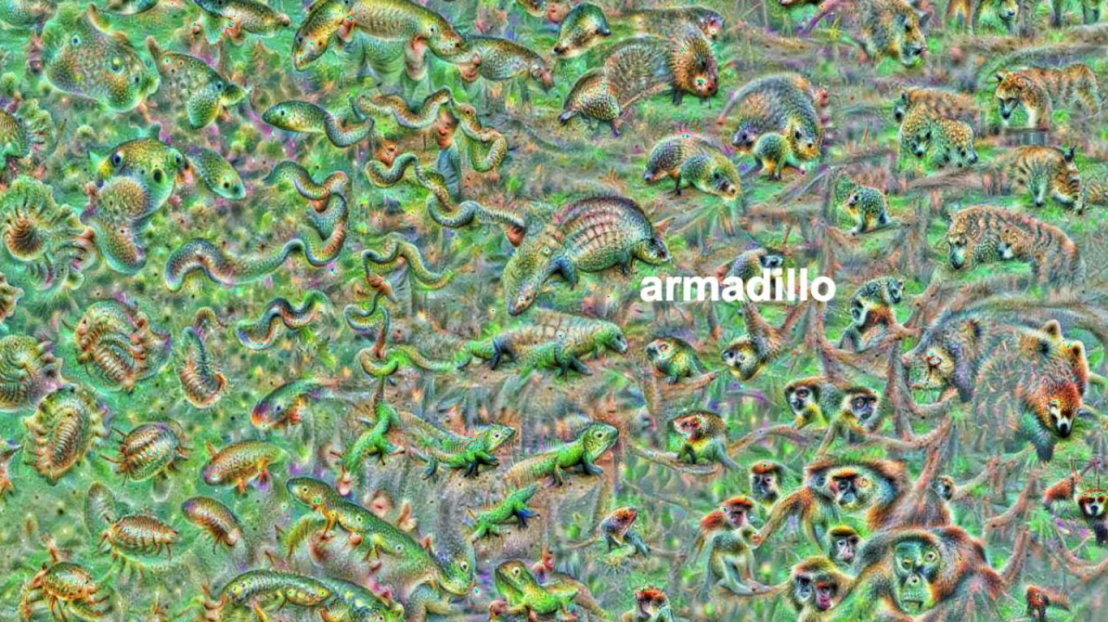

I recently got pointed towards a 2017 paper on bioRxiv that blew my mind: three researchers at the Computational Neuroscience Laboratories at Kyoto, Japan, demonstrate how they trained a deep neural network to decode human functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) patterns and then generate the stimulus images.

In simple words, the scholars used sophisticated machine learning to reconstruct the photo’s their research particpants saw based on their brain activity… INSANE! The below shows the analysis workflow, and an actual reconstructed image. More reconstructions follow further on.

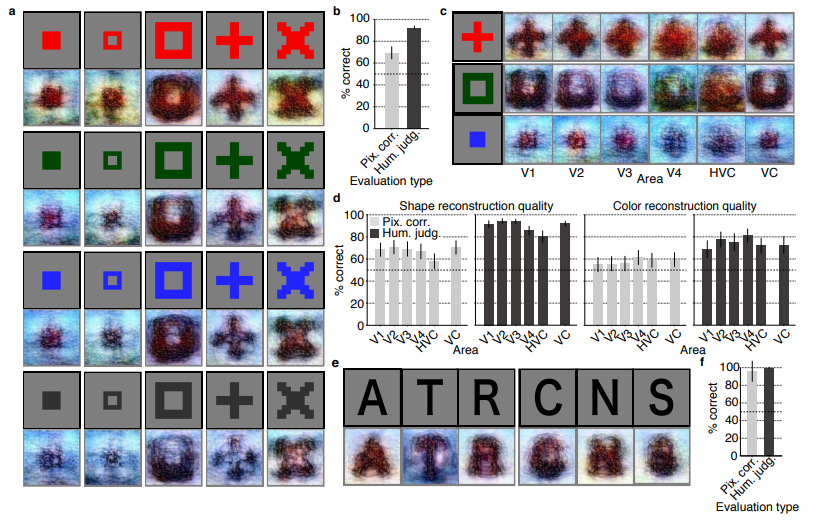

In the image presentation experiments, participants were presented with several natural images from the ImageNet database, with 40 images geometrical shapes, and with 10 images of black alphabetic characters. These visual stimuli were rear-projected onto a screen in an fMRI scanner bore. Data from each subject were collected over multiple scanning sessions spanning approximately 10 months. Images were flashed at 2 Hz for several seconds. In the imagery experiment, subjects were asked to visually imagine / remember one of 25 images of the presentation experiments. Subjects were

required to start imagining a target image after seeing some cue words.

In both experimental setups, fMRI data were collected using 3.0-Tesla Siemens MAGNETOM Verio scanner located at the Kokoro Research Center, Kyoto University.

The results, some of which I copied below, are plainly amazing.

correspond to reconstructions from three subjects. b) Reconstructions with and without the DGN (DNN1–8). The first, second, and third rows show presented images, reconstructions with and without the DGN, respectively. c) Reconstruction quality of seen natural images (error bars, 95% confidence interval (C.I.) across samples; three subjects pooled; chance level, 50%). d) Reconstructions using different combinations of DNN layers (without the DGN). e) Subjective assessment of reconstructions from different combinations of DNN layers (error bars, 95% C.I. across samples) [original]

I can’t even imagine what such technology would imply for society… Proper minority report stuff here.

Here’s the abstract as an additional teaser:

Abstract

Machine learning-based analysis of human functional magnetic resonance imaging

(fMRI) patterns has enabled the visualization of perceptual content. However, it has been limited to the reconstruction with low-level image bases (Miyawaki et al., 2008; Wen et al., 2016) or to the matching to exemplars (Naselaris et al., 2009; Nishimoto et al., 2011). Recent work showed that visual cortical activity can be decoded (translated) into hierarchical features of a deep neural network (DNN) for the same input image, providing a way to make use of the information from hierarchical visual features (Horikawa & Kamitani, 2017). Here, we present a novel image reconstruction method, in which the pixel values of an image are optimized to make its DNN features similar to those decoded from human brain activity at multiple layers. We found that the generated images resembled the stimulus images (both natural images and artificial shapes) and the subjective visual content during imagery. While our model was solely trained with natural images, our method successfully generalized the reconstruction to artificial shapes, indicating that our model indeed ‘reconstructs’ or ‘generates’ images from brain activity, not simply matches to exemplars. A natural image prior introduced by another deep neural network effectively rendered semantically meaningful details to reconstructions by constraining reconstructed images to be similar to natural images. Furthermore, human judgment of reconstructions suggests the effectiveness of combining multiple DNN layers to enhance visual quality of generated images. The results suggest that hierarchical visual information in the brain can be effectively combined to reconstruct perceptual and subjective images.