Daniel Oehm wrote this interesting blog about how to simulate realistic data using a Bayesian network.

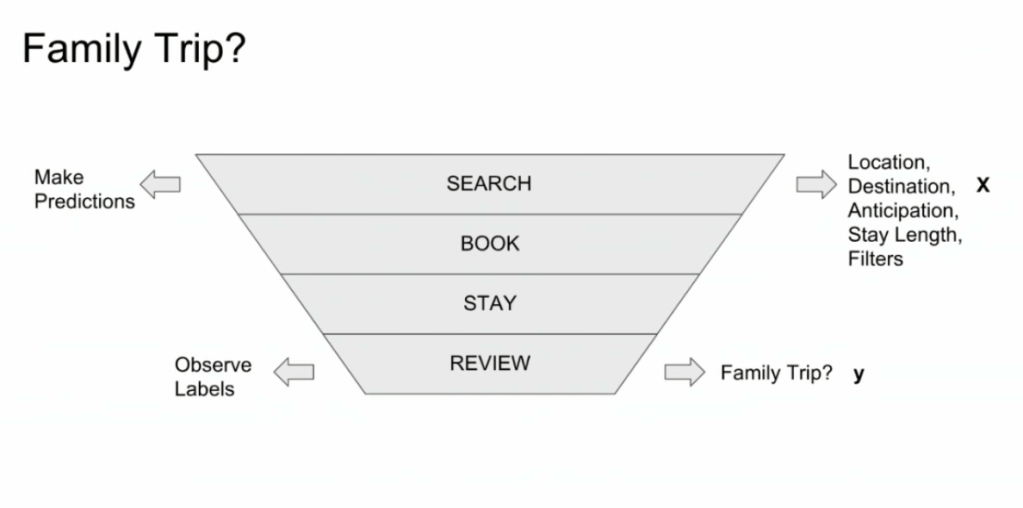

Bayesian networks are a type of probabilistic graphical model that uses Bayesian inference for probability computations. Bayesian networks aim to model conditional dependence, and therefore causation, by representing conditional dependence by edges in a directed graph. Through these relationships, one can efficiently conduct inference on the random variables in the graph through the use of factors.

Devin Soni via Medium

As Bayes nets represent data as a probabilistic graph, it is very easy to use that structure to simulate new data that demonstrate the realistic patterns of the underlying causal system. Daniel’s post shows how to do this with bnlearn.

New data is simulated from a Bayes net (see above) by first sampling from each of the root nodes, in this case sex. Then followed by the children conditional on their parent(s) (e.g. sport | sex and hg | sex) until data for all nodes has been drawn. The numbers on the nodes below indicate the sequence in which the data is simulated, noting that rcc is the terminal node.

Daniel Oehms in his blog

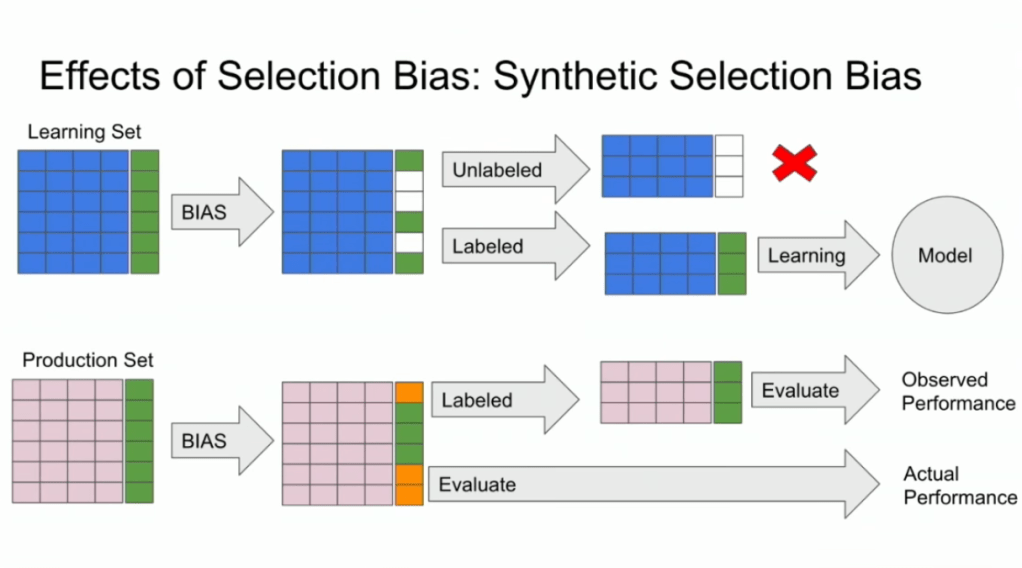

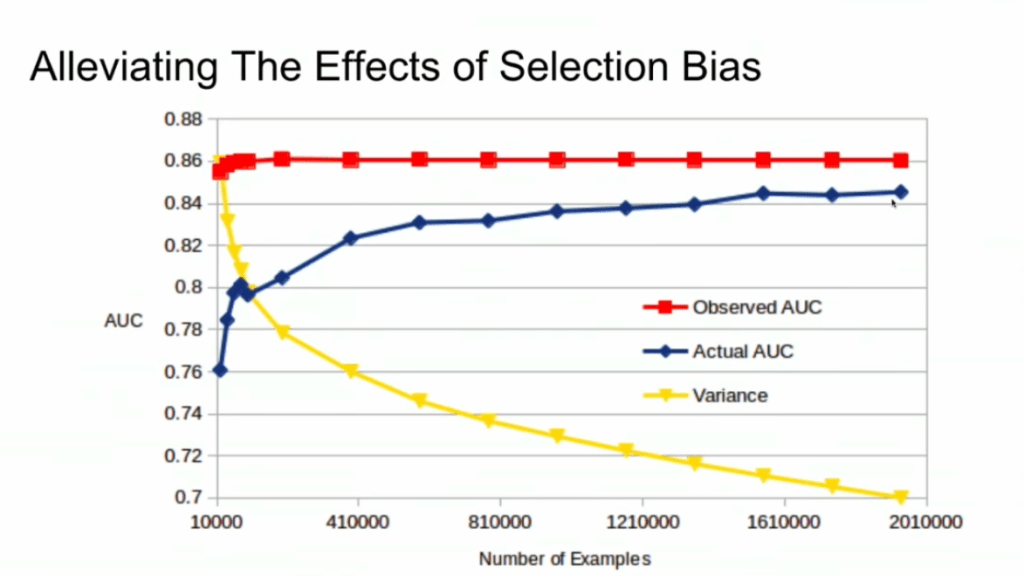

The original and simulated datasets are compared in a couple of ways 1) observing the distributions of the variables 2) comparing the output from various models and 3) comparing conditional probability queries. The third test is more of a sanity check. If the data is generated from the original Bayes net then a new one fit on the simulated data should be approximately the same. The more rows we generate the closer the parameters will be to the original values.

As you can see, a Bayesian network allows you to generate data that looks, feels, and behaves a lot like the data on which you based your network on in the first place.

This can be super useful if you want to generate a synthetic / fake / artificial dataset without sharing personal or sensitive data.

Moreover, the underlying Bayesian net can be very useful to compute missing values. In Daniel’s example, he left out some values on purpose (pretending they were missing) and imputed them with the Bayes net. He found that the imputed values for the missing data points were quite close to the original ones:

In the original blog, Daniel goes on to show how to further check the integrity of the simulated data using statistical models and shares all his code so you can try this out yourself. Please do give his website a visit as Daniel has many more interesting statistics blogs!