Have you ever wondered whether the most active/popular R-twitterers are virtual friends? 🙂 And by friends here I simply mean mutual followers on Twitter. In this post, I score and pick top 30 #rstats twitter users and analyse their Twitter network. You’ll see a lot of applications of rtweet and ggraph packages, as well as a very useful twist using purrr library, so let’s begin!

IMPORTING #RSTATS USERS

After loading my precious packages…

library(rtweet)

library(dplyr)

library(purrr)

library(igraph)

library(ggraph)

… I searched for Twitter users that have rstats termin their profile description. It definitely doesn’t include ALL active and popular R – users, but it’s a pretty reliable way of picking R – fans.

r_users <- search_users("#rstats", n = 1000)

It’s important to say, that in rtweet::search_users() even if you specify 1000 users to be extracted, you end up with quite a few duplicates and the actual number of users I got was much smaller: 564

r_users %>% summarise(n_users = n_distinct(screen_name))

Funnily enough, even though my profile description contains #rstats I was not included in the search results (@KKulma), sic! Were you? 🙂

SCORING AND CHOOSING TOP #RSTATS USERS

Now, let’s extract some useful information about those users:

r_users_info <- lookup_users(r_users$screen_name)

You’ll notice, that created data frame holds information about the number of followers, friends (users they follow), lists they belong to, the number of tweets (statuses) or how many times were they marked favourite.

r_users_info %>% select(dplyr::contains("count")) %>% head()

## followers_count friends_count listed_count favourites_count

## 1 8311 366 580 9325

## 2 44474 11 1298 3

## 3 11106 524 467 18495

## 4 12481 431 542 7222

## 5 15345 1872 680 27971

## 6 5122 700 549 2796

## statuses_count

## 1 66117

## 2 1700

## 3 8853

## 4 6388

## 5 22194

## 6 10010

And these variables that I used for building my ‘top score’: I simply calculate a percentile for each of those variables and sum it all together for each user. Given that each variable’s percentile will give me a value between 0 and 1, The final score can have a maximum value of 5.

r_users_ranking <- r_users_info %>%

filter(protected == FALSE) %>%

select(screen_name, dplyr::contains("count")) %>%

unique() %>%

mutate(followers_percentile = ecdf(followers_count)(followers_count),

friends_percentile = ecdf(friends_count)(friends_count),

listed_percentile = ecdf(listed_count)(listed_count),

favourites_percentile = ecdf(favourites_count)(favourites_count),

statuses_percentile = ecdf(statuses_count)(statuses_count)

) %>%

group_by(screen_name) %>%

summarise(top_score = followers_percentile + friends_percentile + listed_percentile + favourites_percentile + statuses_percentile) %>%

ungroup() %>%

mutate(ranking = rank(-top_score))

Finally, I picked top 30 users based on the score I calculated. Tada!

top_30 <- r_users_ranking %>% arrange(desc(top_score)) %>% head(30) %>% arrange(desc(top_score))

top_30

## # A tibble: 30 x 3

## screen_name top_score ranking

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 hspter 4.877005 1

## 2 RallidaeRule 4.839572 2

## 3 DEJPett 4.771836 3

## 4 modernscientist 4.752228 4

## 5 nicoleradziwill 4.700535 5

## 6 tomhouslay 4.684492 6

## 7 ChetanChawla 4.639929 7

## 8 TheSmartJokes 4.627451 8

## 9 Physical_Prep 4.625668 9

## 10 Cataranea 4.602496 10

## # ... with 20 more rows

I must say I’m incredibly impressed by these scores: @hpster, THE top R – twitterer managed to obtain a score of nearly 4.9 out of 5! WOW!

Anyway! To add some more depth to my list, I tried to identify top users’ gender, to see how many of them are women. I had to do it manually (ekhem!), as the Twitter API’s data doesn’t provide this, AFAIK. Let me know if you spot any mistakes!

top30_lookup <- r_users_info %>%

filter(screen_name %in% top_30$screen_name) %>%

select(screen_name, user_id)

top30_lookup$gender <- c("M", "F", "F", "F", "F",

"M", "M", "M", "F", "F",

"F", "M", "M", "M", "F",

"F", "M", "M", "M", "M",

"M", "M", "M", "F", "M",

"M", "M", "M", "M", "M")

table(top30_lookup$gender)

It looks like a third of all top users are women, but in the top 10 users, there are 6 women. Better than I expected, to be honest. So, well done, ladies!

GETTING FRIENDS NETWORK

Now, this was the trickiest part of this project: extracting top users’ friends list and putting it all in one data frame. As you may be aware, Twitter API allows you to download information only on 15 accounts in 15 minutes. So for my list, I had to break it up into 2 steps, 15 users each and then I named each list according to the top user they refer to:

top_30_usernames <- top30_lookup$screen_name

friends_top30a <- map(top_30_usernames[1:15 ], get_friends)

names(friends_top30a) <- top_30_usernames[1:15]

# 15 minutes later....

friends_top30b <- map(top_30_usernames[16:30], get_friends)

After this I end up with two lists, each containing all friends’ IDs for top and bottom 15 users respectively. So what I need to do now is i) append the two lists, ii) create a variable stating top users’ name in each of those lists and iii) turn lists into data frames. All this can be done in 3 lines of code. And brace yourself: here comes the purrr trick I’ve been going on about! Simply using purrr:::map2_df I can take a single list of lists, create a name variable in each of those lists based on the list name (twitter_top_user) and convert the result into the data frame. BRILLIANT!!

# turning lists into data frames and putting them together

friends_top30 <- append(friends_top30a, friends_top30b)

names(friends_top30) <- top_30_usernames

# purrr - trick I've been banging on about!

friends_top <- map2_df(friends_top30, names(friends_top30), ~ mutate(.x, twitter_top_user = .y)) %>%

rename(friend_id = user_id) %>% select(twitter_top_user, friend_id)

Here’s the last bit that I need to correct before we move on to plotting the friends networks: for some reason, using purrr::map() with rtweet:::get_friends() gives me max only 5000 friends, but in case of @TheSmartJokes the true value is over 8000. As it’s the only top user with more than 5000 friends, I’ll download his friends separately…

# getting a full list of friends

SJ1 <- get_friends("TheSmartJokes")

SJ2 <- get_friends("TheSmartJokes", page = next_cursor(SJ1))

# putting the data frames together

SJ_friends <-rbind(SJ1, SJ2) %>%

rename(friend_id = user_id) %>%

mutate(twitter_top_user = "TheSmartJokes") %>%

select(twitter_top_user, friend_id)

# the final results - over 8000 friends, rather than 5000

str(SJ_friends)

## 'data.frame': 8611 obs. of 2 variables:

## $ twitter_top_user: chr "TheSmartJokes" "TheSmartJokes" "TheSmartJokes" "TheSmartJokes" ...

## $ friend_id : chr "390877754" "6085962" "88540151" "108186743" ...

… and use it to replace those friends that are already in the final friends list.

friends_top30 <- friends_top %>%

filter(twitter_top_user != "TheSmartJokes") %>%

rbind(SJ_friends)

Finally, let me do some last data cleaning: filtering out friends that are not among the top 30 R – users, replacing their IDs with twitter names and adding gender for top users and their friends… Tam, tam, tam: here we are! Here’s the final data frame we’ll use for visualising the friend networks!

# select friends that are top30 users

final_friends_top30 <- friends_top %>%

filter(friend_id %in% top30_lookup$user_id)

# add friends' screen_name

final_friends_top30$friend_name <- top30_lookup$screen_name[match(final_friends_top30$friend_id, top30_lookup$user_id)]

# add users' and friends' gender

final_friends_top30$user_gender <- top30_lookup$gender[match(final_friends_top30$twitter_top_user, top30_lookup$screen_name)]

final_friends_top30$friend_gender <- top30_lookup$gender[match(final_friends_top30$friend_name, top30_lookup$screen_name)]

## final product!!!

final <- final_friends_top30 %>% select(-friend_id)

head(final)

## twitter_top_user friend_name user_gender friend_gender

## 1 hrbrmstr nicoleradziwill M F

## 2 hrbrmstr kara_woo M F

## 3 hrbrmstr juliasilge M F

## 4 hrbrmstr noamross M M

## 5 hrbrmstr JennyBryan M F

## 6 hrbrmstr thosjleeper M M

VISUALIZING FRIENDS NETWORKS

After turning our data frame into something more usable by igraph and ggraph…

f1 <- graph_from_data_frame(final, directed = TRUE, vertices = NULL)

V(f1)$Popularity <- degree(f1, mode = 'in')

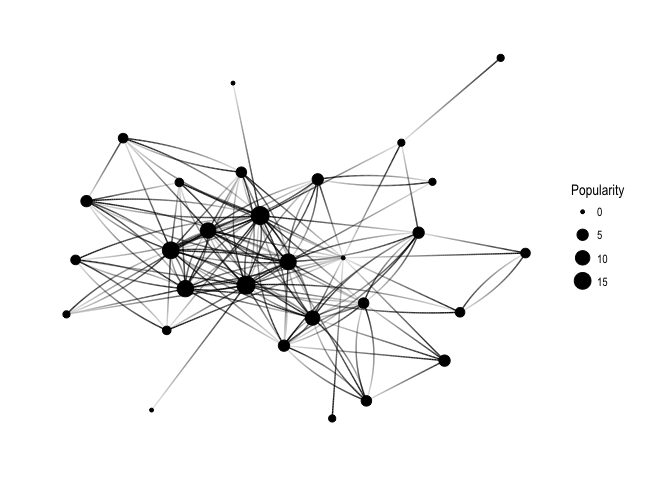

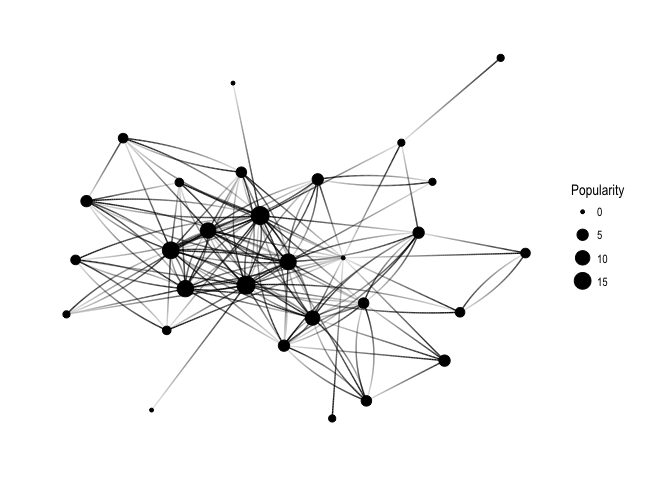

… let’s have a quick overview of all the connections:

ggraph(f1, layout='kk') +

geom_edge_fan(aes(alpha = ..index..), show.legend = FALSE) +

geom_node_point(aes(size = Popularity)) +

theme_graph( fg_text_colour = 'black')

Keep in mind that Popularity – defined as the number of edges that go into the node – determines node size. It’s all very pretty, but I’d like to see how nodes correspond to Twitter users’ names:

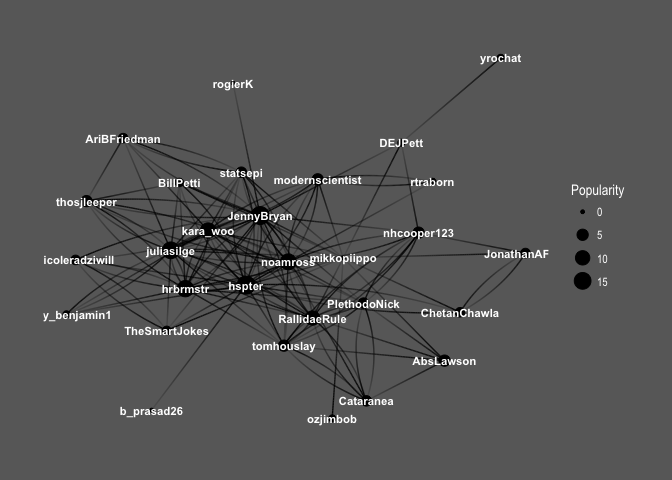

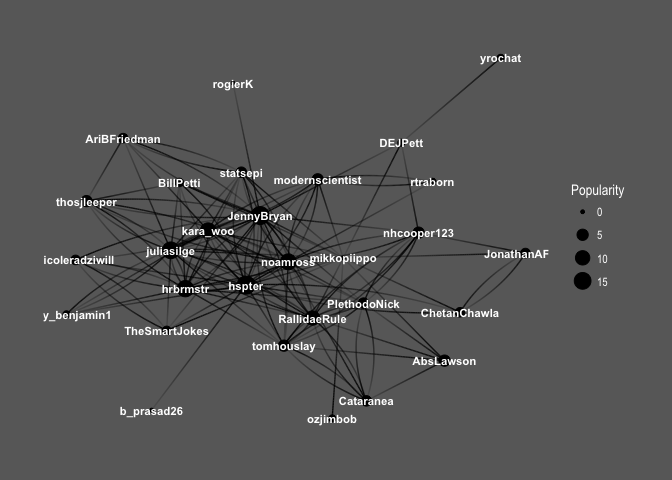

ggraph(f1, layout='kk') +

geom_edge_fan(aes(alpha = ..index..), show.legend = FALSE) +

geom_node_point(aes(size = Popularity)) +

geom_node_text(aes(label = name, fontface='bold'),

color = 'white', size = 3) +

theme_graph(background = 'dimgray', text_colour = 'white',title_size = 30)

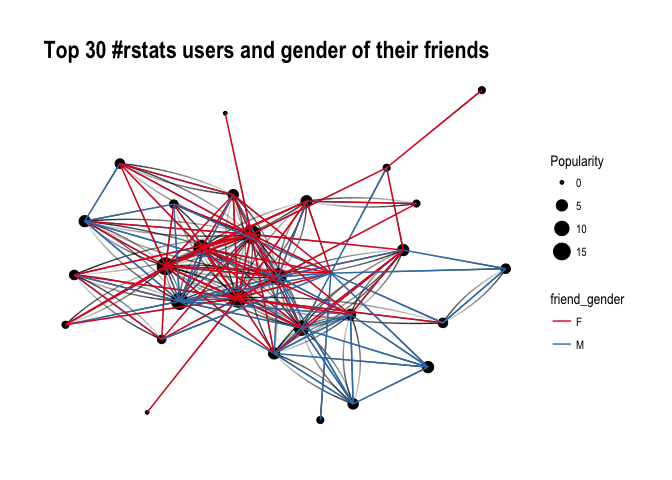

So interesting! You can see the core of the graph consists mainly of female users: @hpster, @JennyBryan, @juliasilge, @karawoo, but also a couple of male R – users: @hrbrmstr and @noamross. Who do they follow? Men or women?

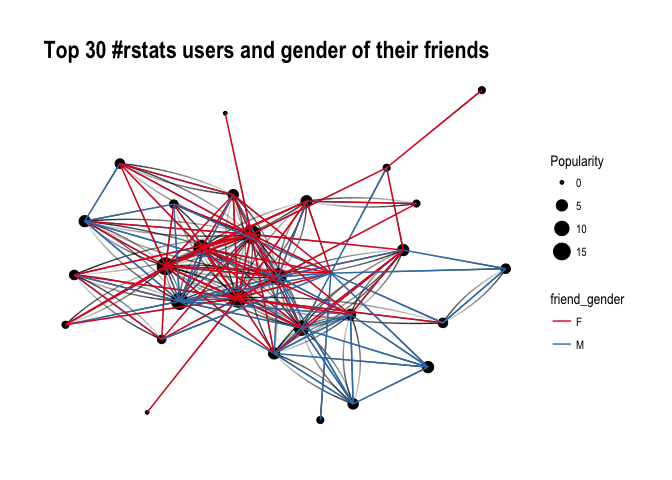

ggraph(f1, layout='kk') +

geom_edge_fan(aes(alpha = ..index..), show.legend = FALSE) +

geom_node_point(aes(size = Popularity)) +

theme_graph( fg_text_colour = 'black') +

geom_edge_link(aes(colour = friend_gender)) +

scale_edge_color_brewer(palette = 'Set1') +

labs(title='Top 30 #rstats users and gender of their friends')

It’s difficult to say definitely, but superficially I see A LOT of red, suggesting that our top R – users often follow female top twitterers. Let’s have a closer look and split graphs by user gender and see if there’s any difference in the gender of users they follow:

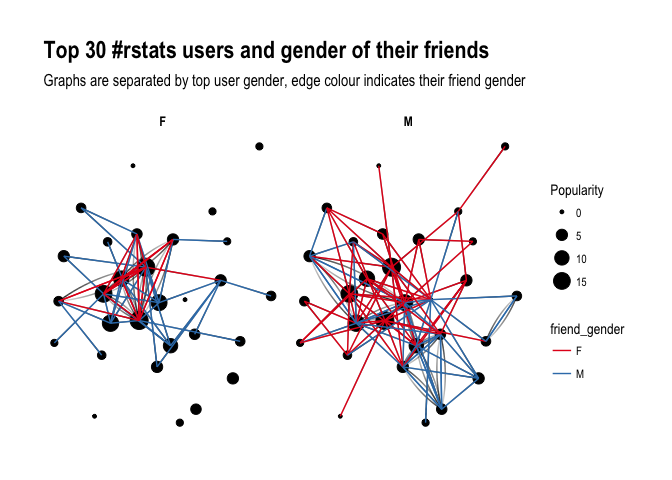

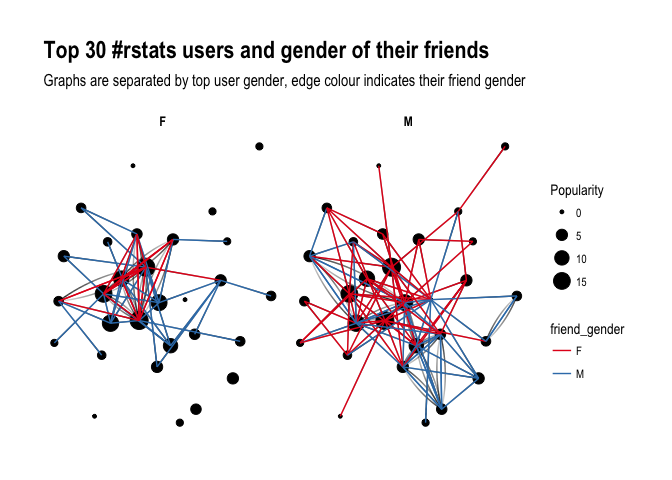

ggraph(f1, layout='kk') +

geom_edge_fan(aes(alpha = ..index..), show.legend = FALSE) +

geom_node_point(aes(size = Popularity)) +

theme_graph( fg_text_colour = 'black') +

facet_edges(~user_gender) +

geom_edge_link(aes(colour = friend_gender)) +

scale_edge_color_brewer(palette = 'Set1') +

labs(title='Top 30 #rstats users and gender of their friends', subtitle='Graphs are separated by top user gender, edge colour indicates their friend gender' )

Ha! look at this! Obviously, female users’ graph will be less dense as there are fewer of them in the dataset, however, you can see that they tend to follow male users more often than male top users do. Is that impression supported by raw numbers?

final %>%

group_by(user_gender, friend_gender) %>%

summarize(n = n()) %>%

group_by(user_gender) %>%

mutate(sum = sum(n),

percent = round(n/sum, 2))

## # A tibble: 4 x 5

## # Groups: user_gender [2]

## user_gender friend_gender n sum percent

## <chr> <chr> <int> <int> <dbl>

## 1 F F 26 57 0.46

## 2 F M 31 57 0.54

## 3 M F 55 101 0.54

## 4 M M 46 101 0.46

It seems so, although to the lesser extent than suggested by the network graphs: Female top users follow other female top users 46% of the time, whereas male top users follow female top user 54% of the time. So what do you have to say about that?

About the author:

Kasia Kulma states she’s an overall, enthusiastic science enthusiast. Formally, a doctor in evolutionary biology, professionally, a data scientist, and, privately, a soppy mum and outdoors lover.

![indico_features_img_callout_small-1024x973[1].jpg](https://paulvanderlaken.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/indico_features_img_callout_small-1024x9731.jpg)