ungeviz is a new R package by Claus Wilke, whom you may know from his amazing work and books on Data Visualization. The package name comes from the German word “Ungewissheit”, which means uncertainty. You can install the developmental version via:

devtools::install_github("clauswilke/ungeviz")

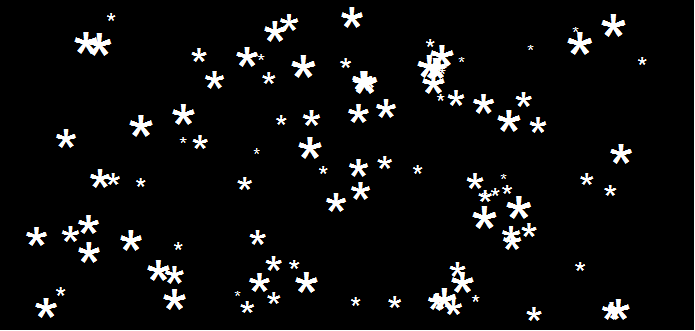

The package includes some bootstrapping functionality that, when combined with ggplot2 and gganimate, can produce some seriousy powerful visualizations. For instance, take the below piece of code:

data(BlueJays, package = "Stat2Data") # set up bootstrapping object that generates 20 bootstraps # and groups by variable `KnownSex` bs <- ungeviz::bootstrapper(20, KnownSex) ggplot(BlueJays, aes(BillLength, Head, color = KnownSex)) + geom_smooth(method = "lm", color = NA) + geom_point(alpha = 0.3) + # `.row` is a generated column providing a unique row number # to all rows in the bootstrapped data frame geom_point(data = bs, aes(group = .row)) + geom_smooth(data = bs, method = "lm", fullrange = TRUE, se = FALSE) + facet_wrap(~KnownSex, scales = "free_x") + scale_color_manual(values = c(F = "#D55E00", M = "#0072B2"), guide = "none") + theme_bw() + transition_states(.draw, 1, 1) + enter_fade() + exit_fade()

Here’s what’s happening:

- Claus loads in the

BlueJaysdataset, which contains some data on birds. - He then runs the

ungezviz::bootstrapperfunction to generate a new dataset of bootstrapped samples. - Next, Claus uses

ggplot2::geom_smooth(method = "lm")to run a linear model on the orginal BlueJays dataset, but does not color in the regression line (color = NA), thus showing only the confidence interval of the model. - Moreover, Claus uses

ggplot2::geom_point(alpha = 0.3)to visualize the orginal data points, but slightly faded. - Subsequent, for each of the bootstrapped samples (

group = .row), Claus again draws the data points (unfaded), and runs linear models while drawing only the regression line (se = FALSE). - Using

ggplot2::facet_wrap, Claus seperates the data forBlueJays$KnownSex. - Using

gganimate::transition_states(.draw, 1, 1), Claus prints each linear regression line to a row of the bootstrapped dataset only one second, before printing the next.

The result an astonishing GIF of the regression lines that could be fit to bootstrapped subsamples of the BlueJays data, along with their confidence interval:

ungeviz, original on its GitHub pageAnother valuable use of the new package is the visualization of uncertainty from fitted models, for example as confidence strips. The below code shows the powerful combination of broom::tidy with ungeviz::stat_conf_strip to visualize effect size estimates of a linear model along with their confidence intervals.

library(broom) #> #> Attaching package: 'broom' #> The following object is masked from 'package:ungeviz': #> #> bootstrap df_model <- lm(mpg ~ disp + hp + qsec, data = mtcars) %>% tidy() %>% filter(term != "(Intercept)") ggplot(df_model, aes(estimate = estimate, moe = std.error, y = term)) + stat_conf_strip(fill = "lightblue", height = 0.8) + geom_point(aes(x = estimate), size = 3) + geom_errorbarh(aes(xmin = estimate - std.error, xmax = estimate + std.error), height = 0.5) + scale_alpha_identity() + xlim(-2, 1)

ungeviz, via its GitHub page